When beauty meets function

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

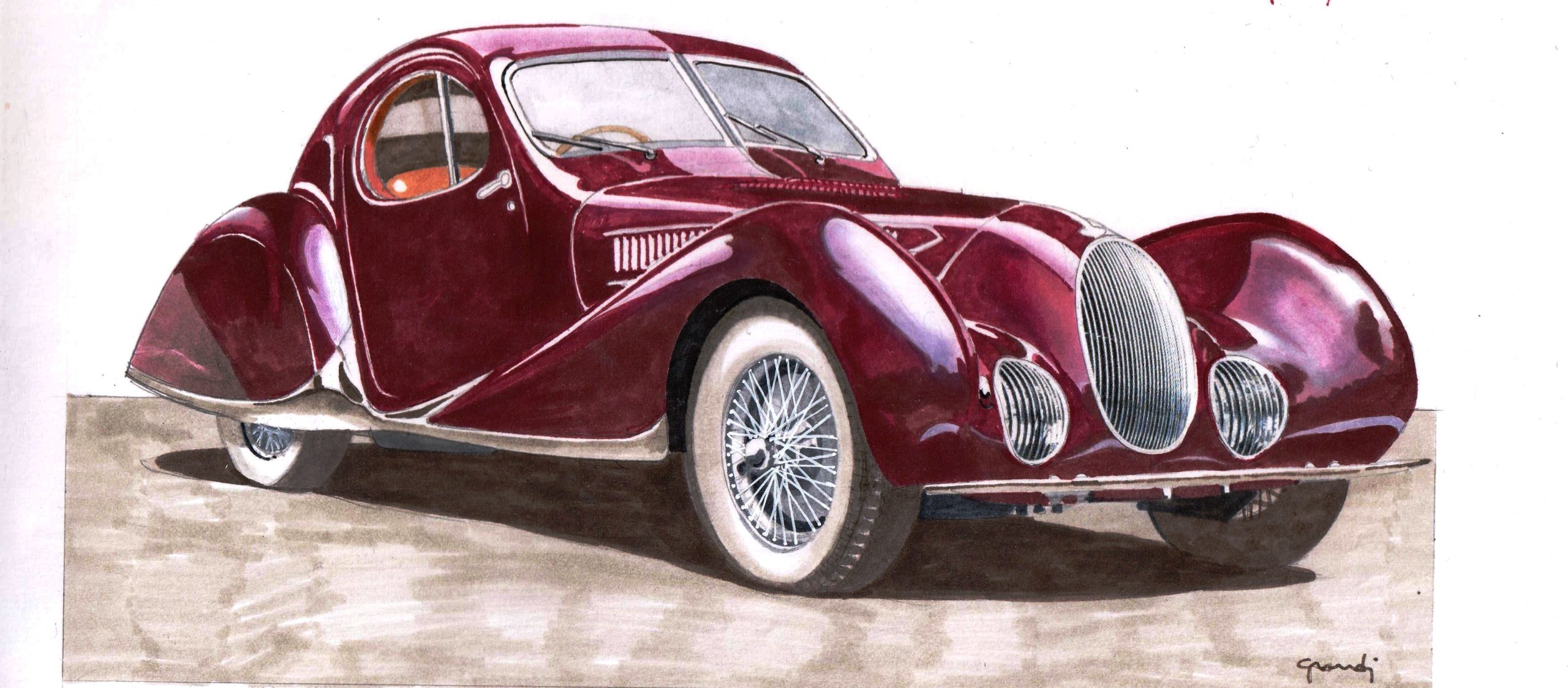

Photo credit: Some images are taken from the book Asi Service "Quando le disegnava il vento" by Massimo Grandi

The leap from function to aesthetics for car designers, was not an easy one. On the one hand, between the 1920s and 1930s, after Jaray had introduced the rules of dynamic efficiency, the public was not yet ready to completely abandon the square vehicles of the time, which were still essentially close relatives of horse-drawn carriages, in favour of cars with flowing, functional lines. In the story described by Massimo Grandi there have been many cases of functional cars that were simply too difficult to sell.

In other words, there have been many illusions created by successes that have never happened. Only in the 1930s, united by some characteristic elements such as very pronounced tails to facilitate the reunification of fluid threads and, at times, by more or less aggressive fins, did cars find their way towards modernity. We have mentioned a few here but invite you to browse the long series of chapters that make up this story, stored in the appropriate “section” of our website.

However, we wish to dedicate a few minutes to those projects that unquestionably left their mark, starting with the British Burney from 1929, inspired by airships with its engine mounted behind the rear axle, the Russian Gaz Aero from 1934 and the magnificent Tatra T77A. However, it was the French who moved aerodynamics forwards by using it as a starting point to create elegant and refined shapes. It is by no coincidence that the term “French curves” became ubiquitous after Dubonnet’s experiments with his Dolphin from 1935, Jean Andreau‘s Peugeot 402 and The Labourdette from 1936. However, French curves reached their zenith with those cars built primarily to amaze. Just three examples are enough to illustrate this point: the Bugatti Atlantic, the Delahaye 165M and the Talbot Lago “Goutte d’Eau”.

During this period, the Americans and Germans were hardly sitting on the side lines: whereas the BMW 328 Wendler Stromlinien was designed for efficiency, the American Phantom Corsair looked towards the future. Tastes had now changed but designers had to wait for the end of the Second World War to begin the era we know today.