Who killed Ettore Bugatti?

Photo credit: Bugatti, Wheelsage, Hemmings

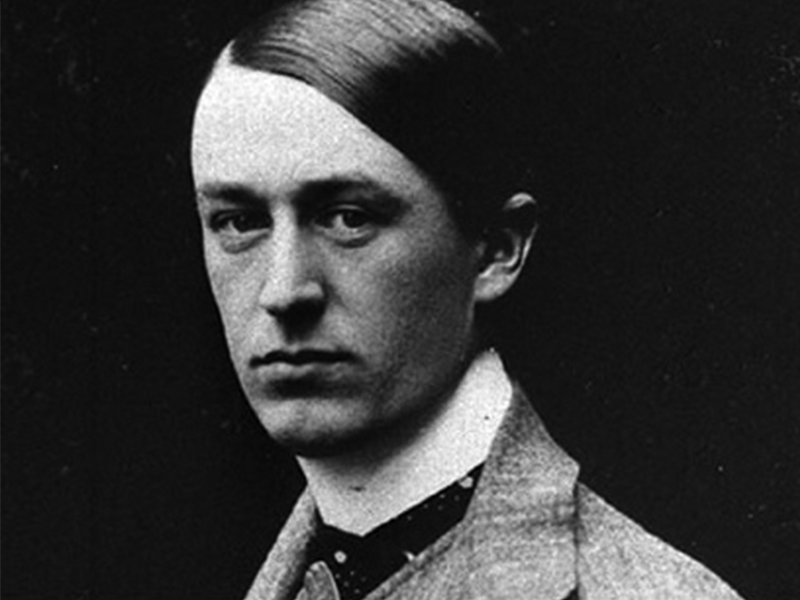

Elegant and aristocratic, an artist at heart – just like his brother Rembrandt who cast magnificent bronze statues like the elephant on the radiator of the Royale – but an engineer by craft. A stubborn engineer at that, able to invent extraordinary things but, at the same time, stubborn in not wanting to accept innovations that would help the performance of the very special cars he designed and built.

Cars of a characteristically deep blue, inspired by the blue of the French flag, although he was Italian and remained so to the end, which caused him one of the many problems that turned the tide on his magnificent life. His parents were visionary cabinetmakers and jewellers. Their eclectic and oriental-inspired furniture, with their distinctive art deco styling, are now desirable collector’s items. But Ettore preferred metal to wood. He preferred it so much he presented his first car before the age of twenty. The second, when he was 21, awarded at the 1901 Milan Expo which took him to the country where he became famous, France or rather, to that territory disputed for years between the French and the Germans called Alsace.

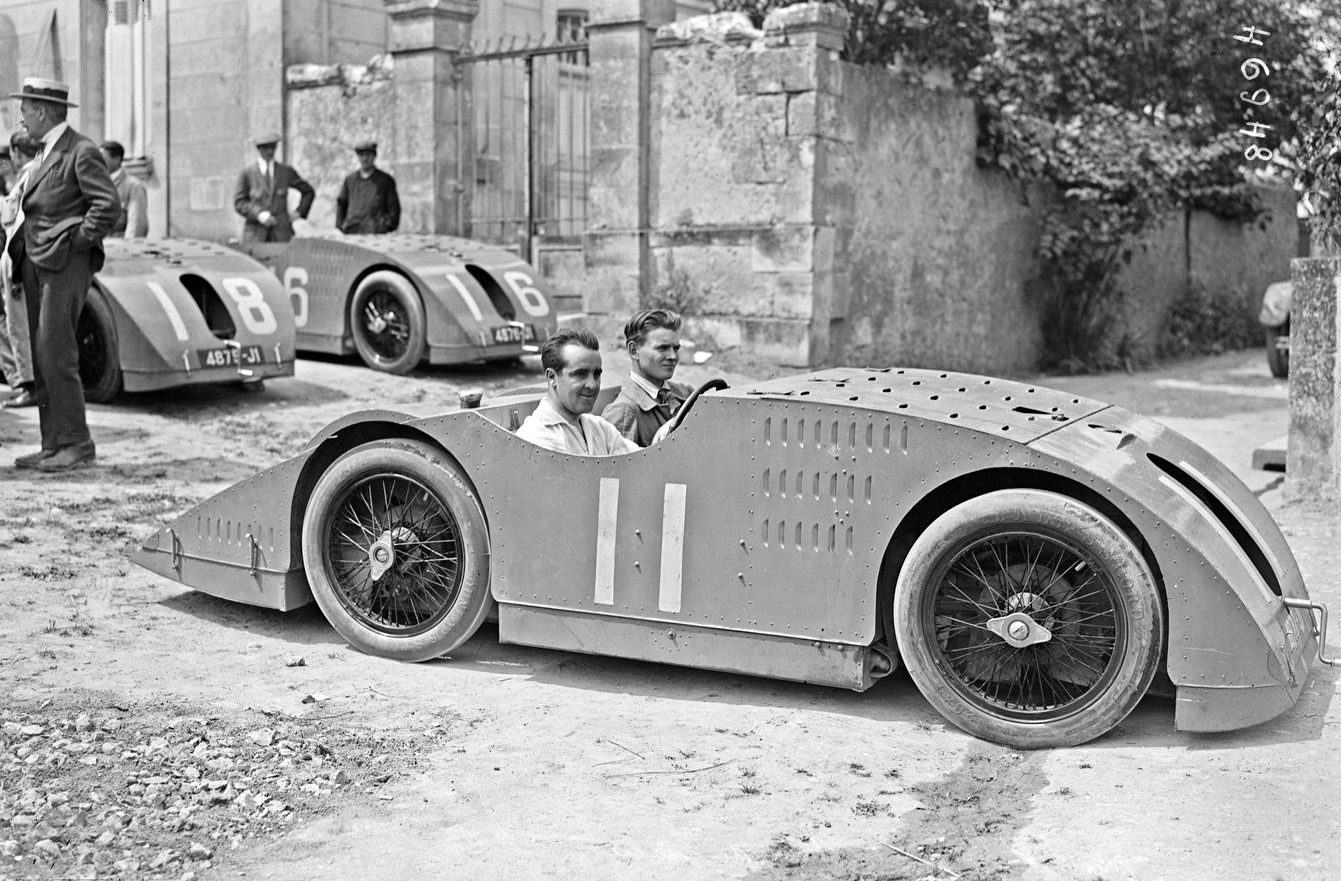

When he realized that his destiny was to build cars at the age of 28, he created his studio in Molsheim where the cars that bear his name are still built to this day: Bugatti. Success in racing, where the Bugattis had begun to dominate even before the First World War with the Type 13, and where they had become undisputed champions, winning practically everywhere, above all in the 20s when Art Deco reigned supreme in France, had given him notoriety and well-being. Not only did the Bugattis win races with their aristocratic radiators that, erroneously, many believe is inspired by a horseshoe when, in reality, it was the reproduction, personally designed by Ettore, of one of the two arches in front of the steps leading to the town hall in Molsheim, they were increasingly perceived as an authentic status symbol for the road.

Ettore Bugatti, like all true visionaries, had created his own style. A style that he himself transmitted to his precious products and that had come to make him produce, complete a chassis number as if they were real cars, the Type 35 small scale model for the children of his customers. The perfect little car had opened the gates of the mansions of ruling houses, great industrialists and heads of state with whom, he himself, often had relationships. This obsession with magnificence ranged from his factories, perfectly equipped with state-of-the-art machinery, often designed by himself, to his sumptuous home where coveted parties were held, and to the racing circuits where, already in the 20s, set up tents for his guests and for his drivers, and even equipped them with showers!

His genius expanded across most diverse of fields, including the Air Force during the First World War and fast rail transport with high-speed trains which, in the 1930s, in use on the French railways, exceeded 170 kilometres per hour. Over the years he had found a magnificent sidekick in the talent of his son Jean, a passionate engineer and his perfect heir. Thanks to Jean, models were created that fascinated the entire world such as the famous Atlantic, the majestic Royale, and the Type 57 that competed in and won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1937 and 1939.

What more could a man want from life? It’s hard to know if Ettore ever asked himself this question. Of course, when everything is so magical and perfect, tragedies are all the more dramatic. On 17th June 1939, Bugatti won again at Le Mans with the Type 57 Tank, on 11th August Jean Bugatti organized a road test with that car – on roads held virtually closed by some volunteers. He was behind the wheel himself, and it wasn’t the first time. And it is Jean who, in an attempt to avoid a mysterious cyclist who came from nowhere, crashed into a tree and died on the spot under the eyes of his younger brother Roland who helped stop the traffic. Imagine the heartbreak of his father who had already experienced the pain of his brother Rembrandt’s suicide.

Three weeks later, the German army invaded Alsace and took over the Bugatti plants. Ettore, fearing this fact, had anticipated the threat by transporting much of the machinery to Bordeaux, but it was not enough. The invaders found him and demanded that he cooperated by producing torpedoes and cars for the German army. he refused. He had also run up some steep debts and agreed to sell the company and the machinery for a sum that was less than 50% of its value.

He fled with his family to Paris and tried to put his pain behind him by designing torpedo boats and aviation engines. That found no use in occupied France. He was Italian and had never sought French citizenship. At the end of the war the French state did not support him and, indeed, in the name of what had been fascist Italy allied to the Germans, was even accused of collaboration with the German occupiers. This magnificent man, the prince of the automobile and racing, demoralized and depressed, found himself without anything at the end of the war: his factory, now French, was not returned to him. He sued the state but lost. He was dismayed. He visited Molsheim, saw the factory in ruins, his villa abandoned, the place where Jean died. It was a fatal blow: his health deteriorated but he did not give up, became a French citizen and finally took possession of what rightfully belonged to him.

It’s now June 1947, he’s 66 years old but unrecognizable. After contracting a lung disease, he also suffered a stroke. Yet just that month, on the 11th to be exact, Ettore Bugatti was rehabilitated, and his possessions were returned to him. But has was unable to enjoy this much hoped-for news, as his condition was now very serious. On 21st August, he died leaving a veil of sadness that will remain in everyone who admired and loved his genius.