Photo credit: Wheelsage

Jim Hall is part of a very small group of racing engineers who brought important and long-lasting evolutions to the world of motor sport. The son of a family of American oil producers, Jim Hall started out as a driver before becoming a manufacturer, which gave him plenty of opportunities to exploit a close relationship with the technical management of GM.

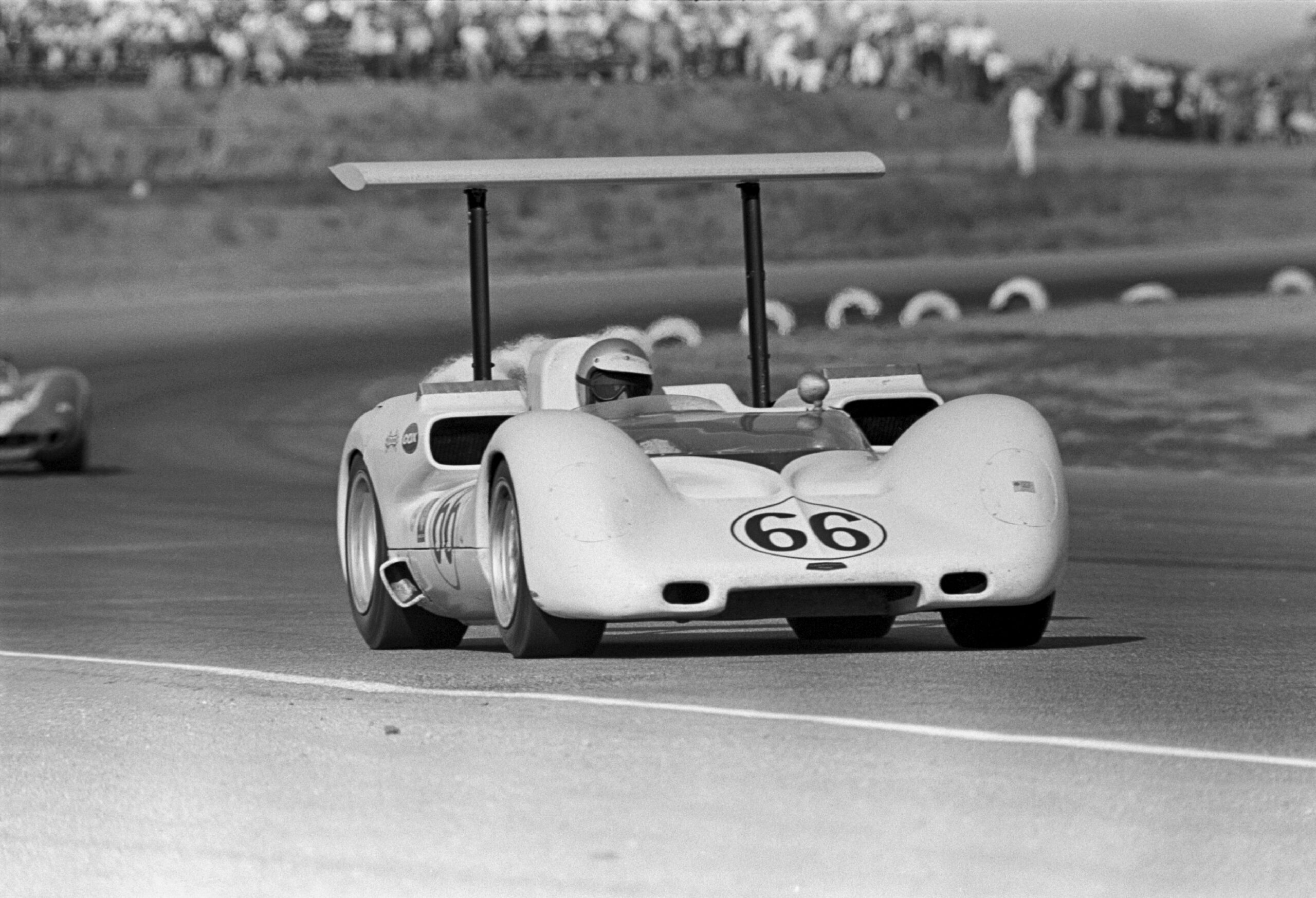

When he decided to abandon his driving ambitions, for which he had also begun to build his own sports cars called Chaparral, he devoted himself to the continuous and fruitful application of technical and aerodynamic innovations that brought the entire motoring industry to a turning point. Taking advantage of GM’s wind tunnel, in 1963 he had already introduced intelligent modifications to his Chaparral 2A with very visible aerodynamic appendages to increase front-end grip around the circuit. This experience was developed further in 1966 with the 2E which featured a large rear wing attached directly to the rear suspension uprights, loading the tyres for extra adhesion while cornering.

What seemed like an extravagance transformed into a veritable revolution that led to the current use of aerodynamics to increase car performance far beyond racing. Jim Hall, who developed his activities both in Europe, in the Sport Prototypes Championship, and in America, in the Can-Am Championship (from Canada to America) in those years, made full use of GM’s research into production cars, transferring data and insights to the world of competition.

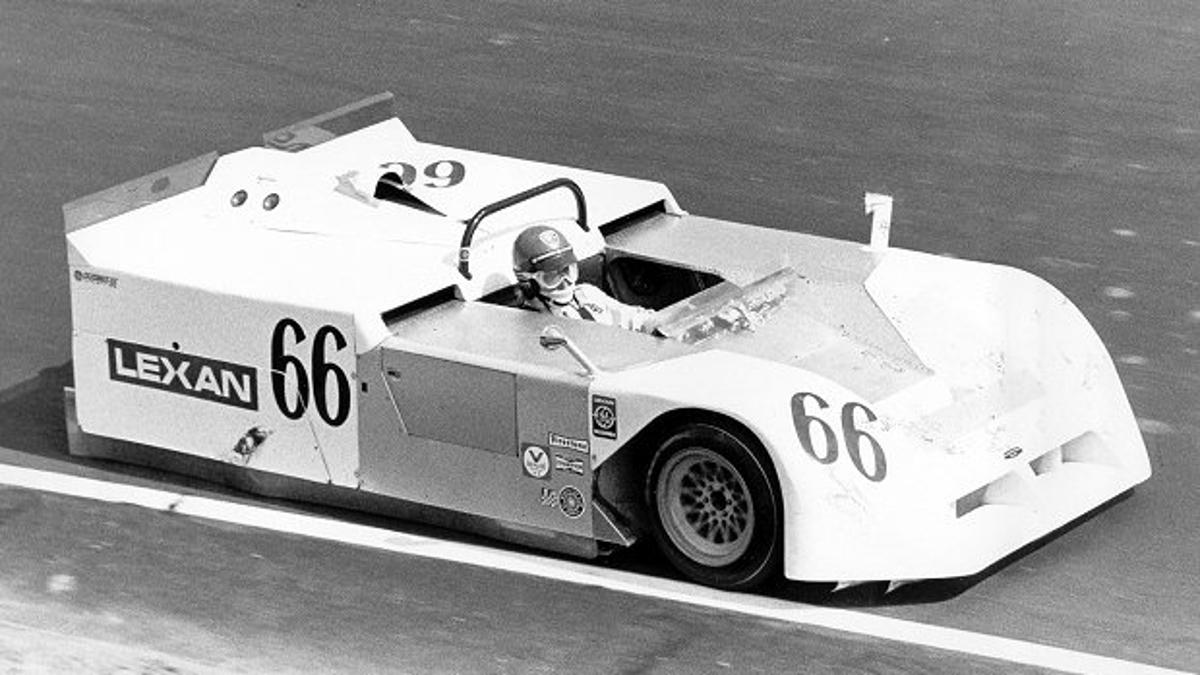

These exploits reached new heights when, in 1970, he entered the Chaparral 2J in the Can-Am races, cars that sealed the air beneath the car using what we now call the miniskirt effect, extracting it with two fans housed at the rear to create truly incredible levels of downforce.

As incredible as it seems – and it is well documented for all you non-believers – this further step forward in the history of aerodynamics was inspired by the experiments that GM was carrying out on its Corvair production model, which had been criticized by the media for poor road holding. To correct this inconvenience, GM technicians had noticed that by sealing the air beneath the car by lowering the sides, it became more stable. An impractical solution for road use, but one that gave Jim Hall the idea of bringing the ground effect principles to racing with the 2J.

Curiously, these great innovations soon became a part of the heritage of Formula 1, with Ferrari being the first to mount a wing on its 312 F1, and Lotus dominating with the 79 which exploited ground effect to the max. The exploits of Chaparral have largely been forgotten, but if today motoring has come so far, much of the merit is due to this small but very courageous American manufacturer.