The Speed Record Story

6 – Forward momentum, despite the tragic War

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

After the appearance of extraordinary vehicles such as Henry Segrave’s Golden Arrow and Malcom Campbell’s Bluebird, the race for the world land speed record became an exciting challenge for the general public. Curiosity was ardent: who would be the first to break the 500 km/h barrier? The challenge, moreover, was an all-English affair with the arrival of two new contenders, George Eyston with his Thunderbolt and John Cobb with his Railton. This speaks volumes about the British and their passion for the automobile.

It was 1937 when George Eyston first broke the 500 km/h barrier in the official time trial on the Bonneville Salt Flats, in the USA. His six-wheeled Thunderbolt, with its twin steering front axles, fitted two Rolls Royce engines that transmitted power to the rear wheels: The thunderbolt’s true handicap was its mammoth weight of some 7 tons. The unpainted aluminium body played a curious joke on Eyston too: in the first attempt, the reflection of the sun on the bodywork of the car, similar to those created by the lake, did not allow the speed to be detected and they had to repeat the test!

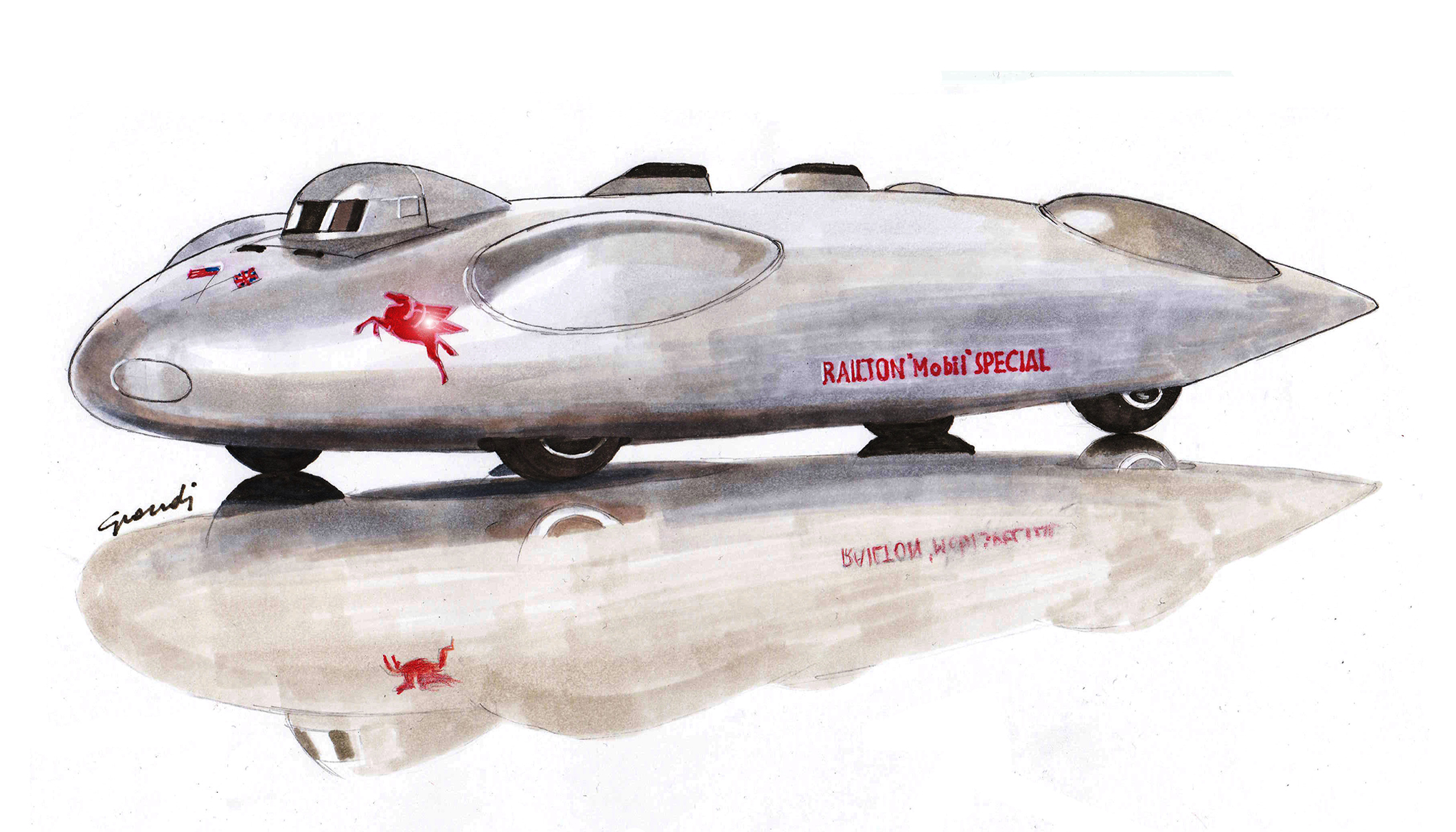

One year later, Eyston, who in the meantime had improved the engine cooling system, reached 555 km/h but, just one month later, John Cobb ousted him to claim the record at 564 km/h. Cobb had the advantage of much more advanced technology: his Railton had four-wheel drive and its two Napier Lion W12 engines transmitted power to the wheels through two longitudinal shafts. All told, the car weighed just over three tons.

The very next day, however, Eyston managed to regain the record once more by travelling at 575 km/h but Cobb, in subsequent attempts, was unreachable arriving at an incredible 595.041 km/h in 1939 – bear in mind that the air speed record was 755 km/h, held by a single-engine Messerschmitt – and then 634.398 km/h in 1947. As the war technology progressed during the same period, the air speed record rose to 1047.356 km/h with the Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak and the very first jet aircraft experiments, which took mankind very close to the speed of sound.

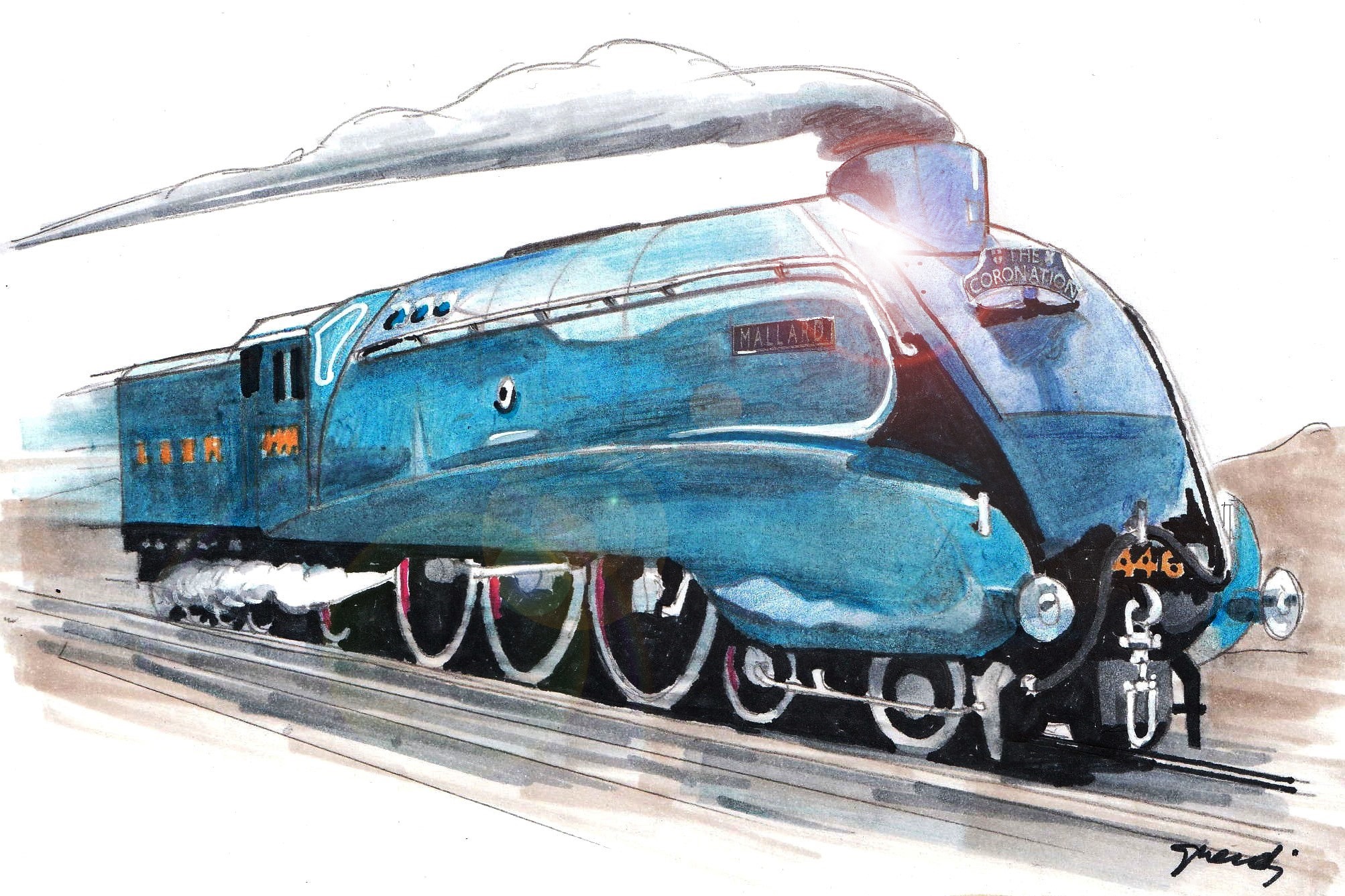

Great progress had also been made in motorcycles, with the NSU Delphin Streamliner 1 and its very small 499cc engine reaching 290.322 km/h in 1951 and in railways, where the American Pennsylvania Railroad class S2 with its steam turbine engine reached 177 km/h. Not much, in reality, when compared with the final record for a steam locomotive, the British-built Mallard, which thundered along at speeds beyond 202 km/h in 1938, a record that still stands to this day.

The England-Germany challenge for the land speed record was missing, however. Everything was ready, but it would never take place: Mercedes, under the technical direction of Ferdinand Porsche, had made a six-wheeled vehicle driven by a supercharged V12 Daimler-Benz DB 603 aircraft engine, capable of producing 3,000 horsepower with a disproportionate displacement: 44,500cc! When everything was ready, the outbreak of war blocked the program and the T80, this is its acronym, was destined for the Mercedes museum where it can still be seen today.

The British also dominated on water in those years: in 1939, Malcom Campbell, with Bluebird K4 reached 228.11 km/h. A record that would stand for 11 years…