The Speed Record Story

7 – Beyond the speed of sound

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

We have covered the history of those daredevils who dreamed of being the world’s fastest person in a land-based vehicle. Many rejoiced. Others sacrificed their lives for an ephemeral dream. Along the journey, we’ve seen on numerous occasions that the moment a new record was set, someone came along and broke it. Above all, we have witnessed the extraordinary progress of the technologies and the engines used in the pursuit of ultimate speed.

With the Second World War, an era ended: the one that featured driven wheels and internal combustion engines. The arrival of jet engines and even rocket propulsion forever changed the history of post-war records. The last flame of tradition – in 1964 – came in the form of Donald Campbell, Malcom’s son who, just like his father, had been dragged into this eternal land- and water-based contest. Just like his father, he too set records in both disciplines: land and water but died in 1967, at the age of 46, while attempting to exceed the maximum speed on the Bluebird K7 speedboat which, at the time of the accident, was travelling in excess of 480km/h.

On land in 1964, Donald took his Bluebird with its 4,000 horsepower Proteus engine originally intended for turboprop aircraft, to 648 km/h. The wheels, however, were driven and the dream of the 800 km/h remained just a dream. In fact, the climb to the record was also hindered by a terrible accident that caused serious injuries to Donald. But he refused to give up writing his name in the golden register. And he succeeded.

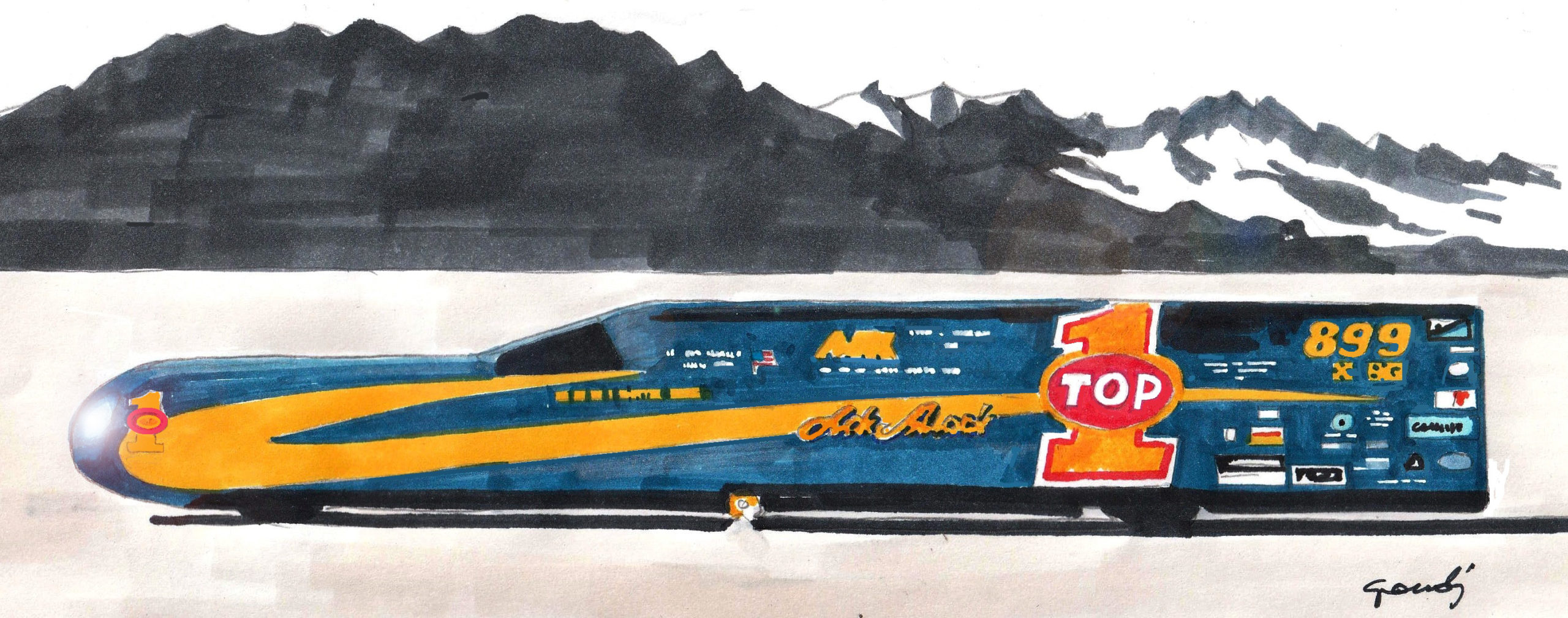

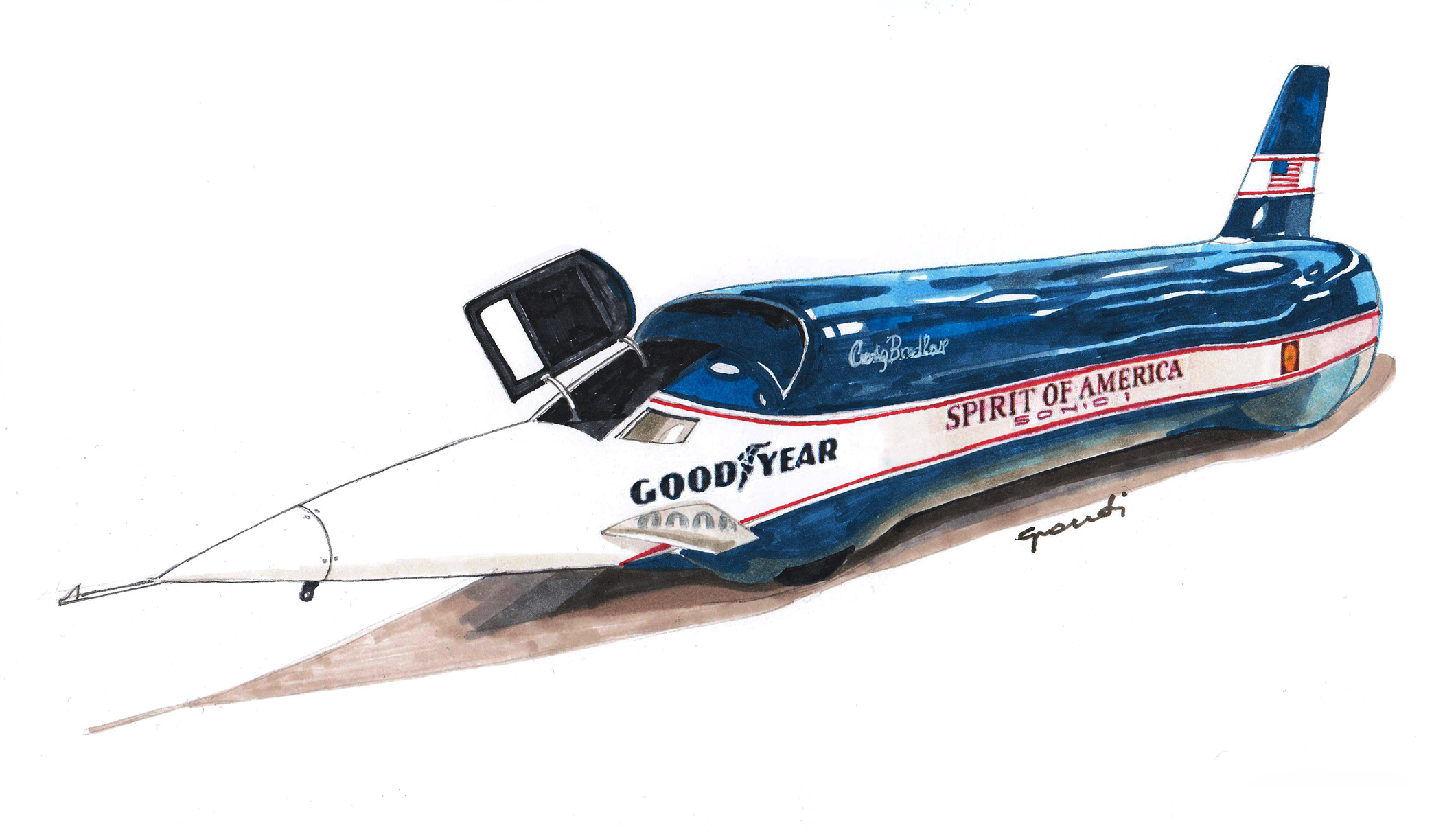

This was, however, destined to be the end of the British-led record run. The Cold War had ushered in an ideological conflict between the United States and the USSR that extended to the most spectacular of world firsts. The Russians launched Sputnik in 1957 and America had been caught off guard and momentarily lost its technological leadership. As a result, any record they could claim softened the blow. In 1965, The Spirit of America broke the 1,000 km/h barrier and the dream of breaking the sound barrier was now tantalisingly close.

This record was finally broken in 1997, with the Thrust SSC supersonic car equipped with two afterburning Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines, that reached 1,227.986 km/h.

But let’s take a step back: after Campbell, during the development of the Spirit of America, in 1964 the Wingfoot Express reached 668 km/h and, just three days later, on 5th November 1964, the Green Monster reached 699 km/h. This led to the challenge with Spirit of America. In 1965, the Green Monster reached 921.423 km/h but once again this was beaten by Spirit of America at 966.573 km/h, just eight days later.

The two vehicles were powered by turbojet engines: the first by the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter and the second by the engine from the F86 Sabrejet, both made by General Electric.

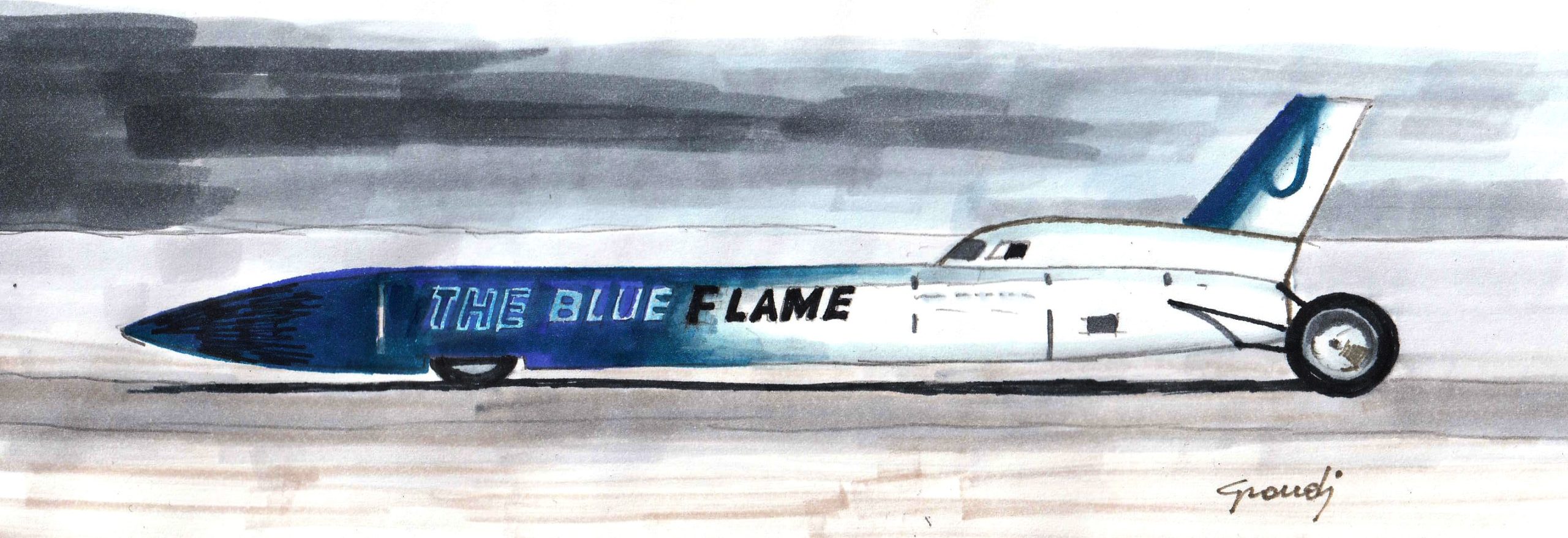

Five years later, however, a rocket-engine spoiled the party, when the Blue Flame exceeded the 1,000 km/h barrier for the very first time.

Another gap, this time more than ten years, and in 1983 a new record was set by Thrust2

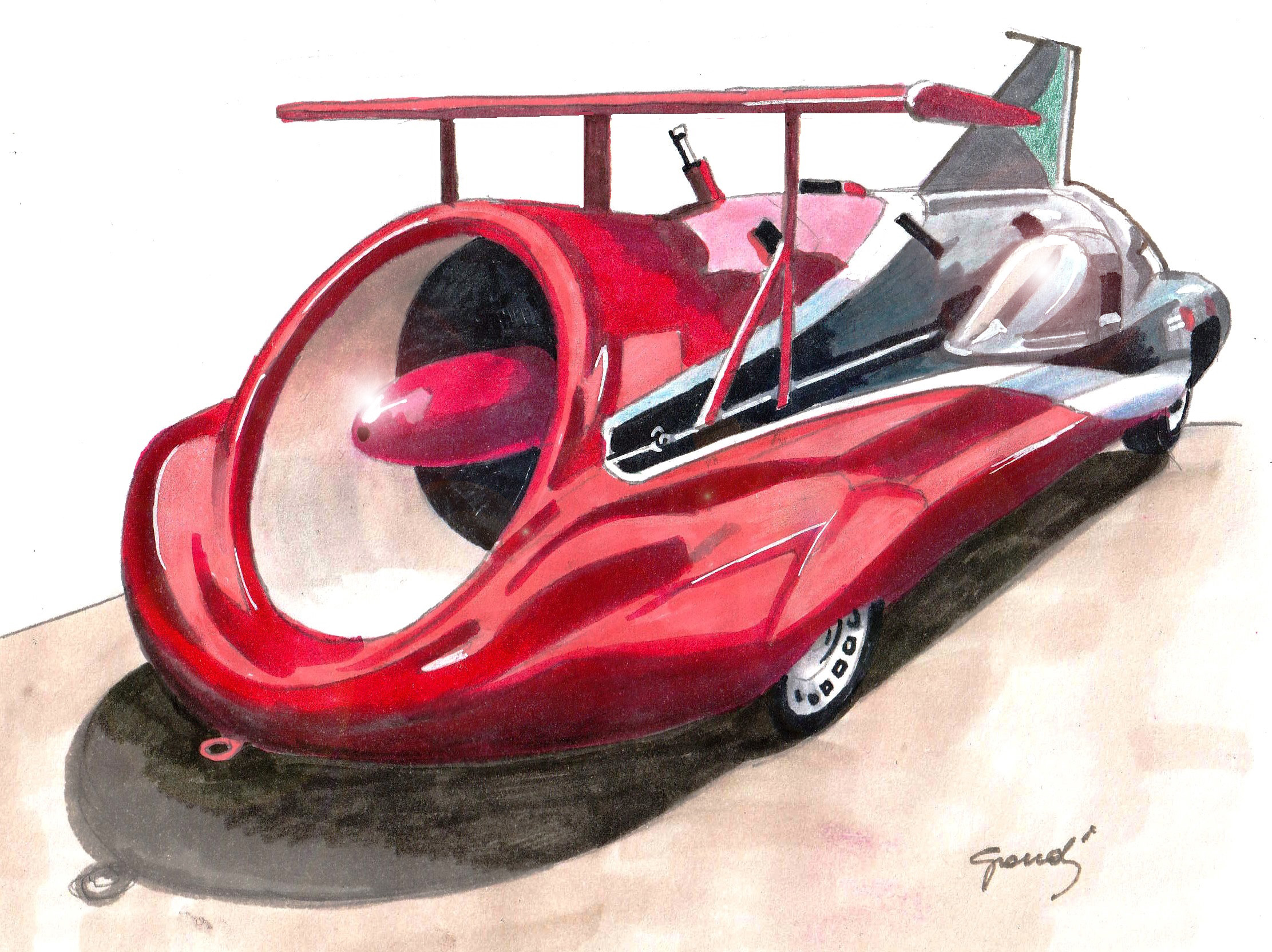

powered by a Rolls-Royce jet turbine engine which raised the record by just 6 km/h. That was too little and the decision was taken to commission a new Thrust, christened SSC, which had the sound barrier clearly in its sights. There were now two Rolls-Royce engines, producing a frankly scary one hundred and two thousand horsepower! At its second attempt in 1997, Trust SSC set the current record. Who’s next? Of course, there will be one, because this race against the unknown simply cannot end.

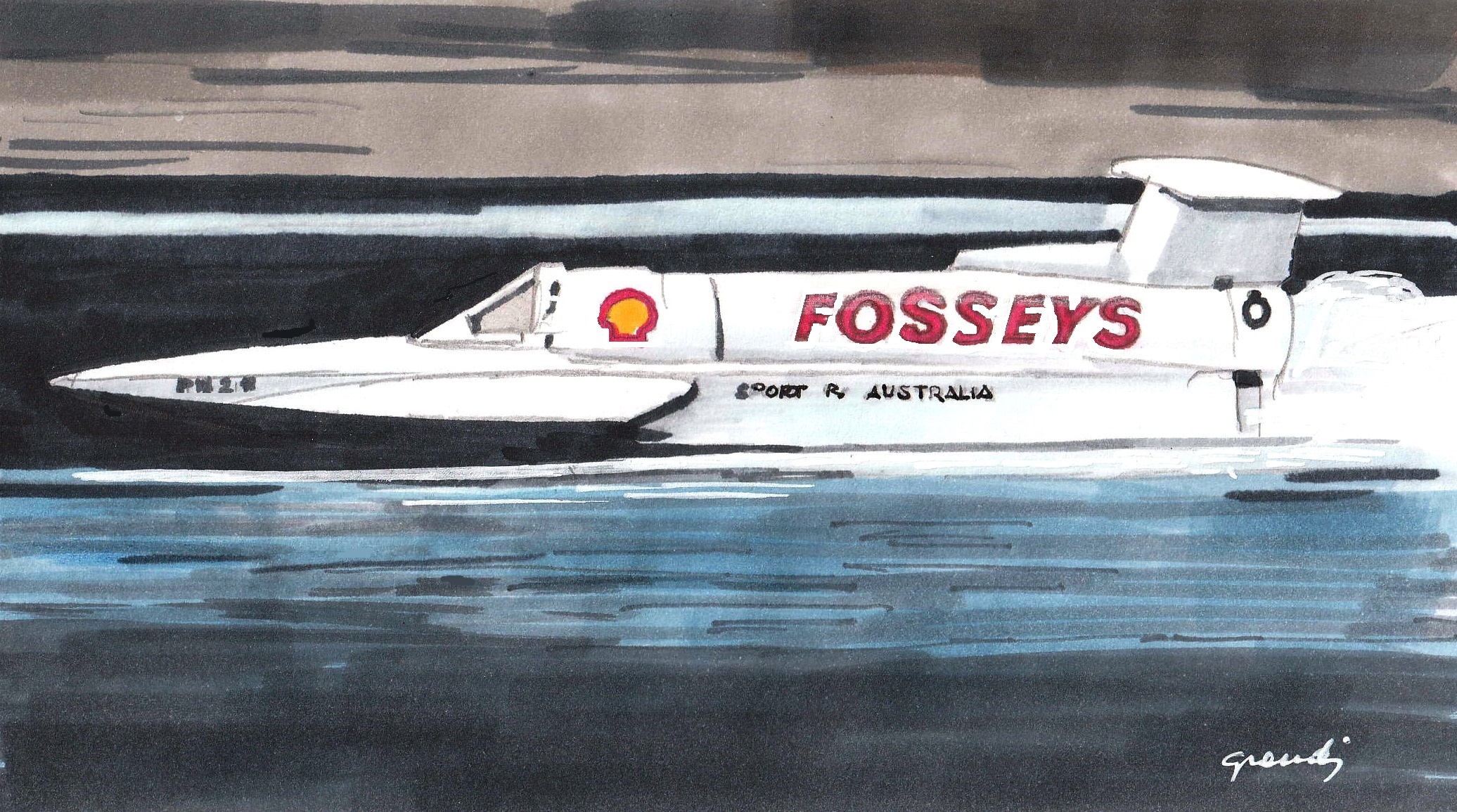

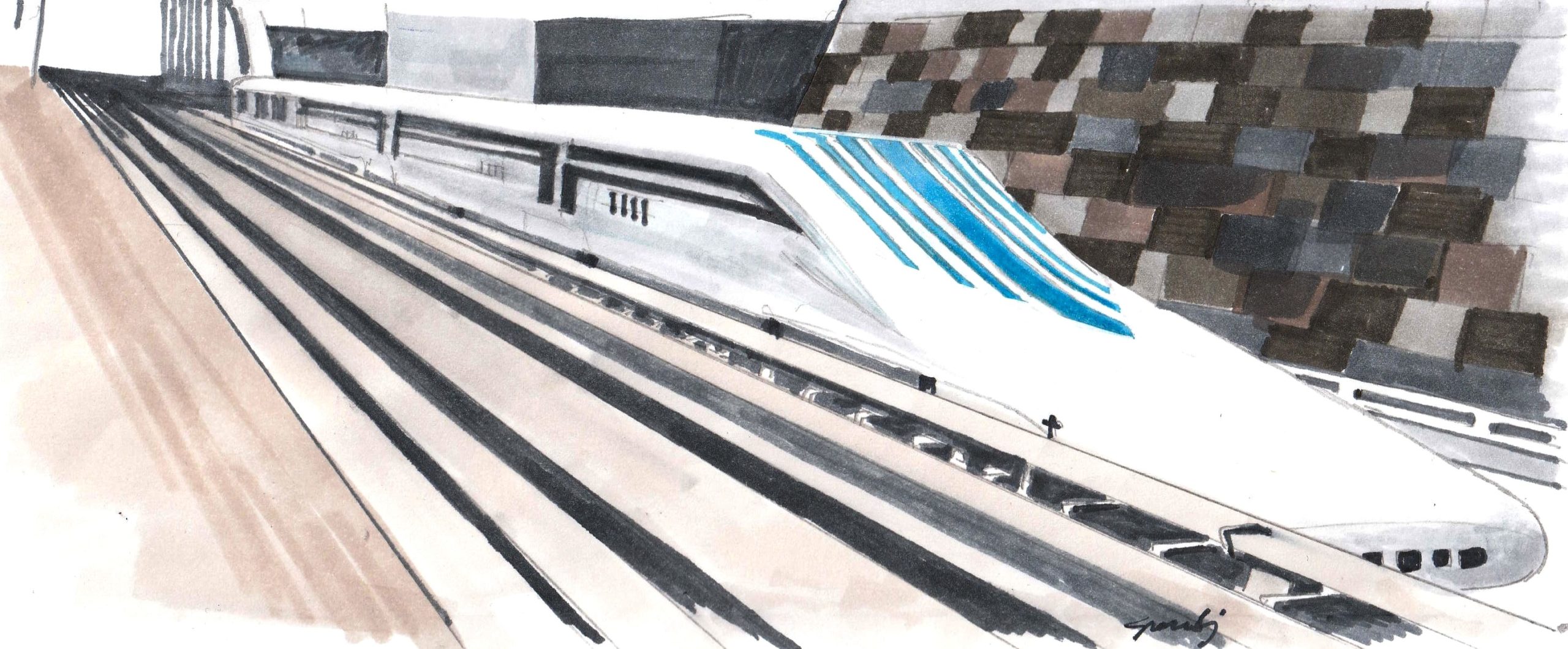

And the others? Currently the fastest boat is the Spirit of Australia at 511.121 km/h, the fastest train is the Japanese L0 magnetic levitation train, at 603 km/h and motorcycles, incredible but true, stand at 605.697 km/h.