The Speed Record Story

4 – 250 kilometres per hour. The final victory of fantasy

After 1925, it was technology that took the car to 500 km/h. With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

Just as engineers figured out that for vehicles destined to break speed records, Otto cycle internal combustion engines were the winning solution, the 200 km/h barrier was broken – not without surprise – by a steam-powered car. With careful attention to the aerodynamics in a similar vein to the Baker Torpedo – a sort of upside-down canoe that partially resembled the shape of a teardrop – the Stanley Rocket used a twin-cylinder engine capable of producing 150 horsepower and on 26th January 1906, on Daytona Beach, it managed to reach 205.448 Km/h. 58 years would then pass before a non-combustion engine could once again reclaim the record. That was a turbine engine which was followed by jet-powered ones.

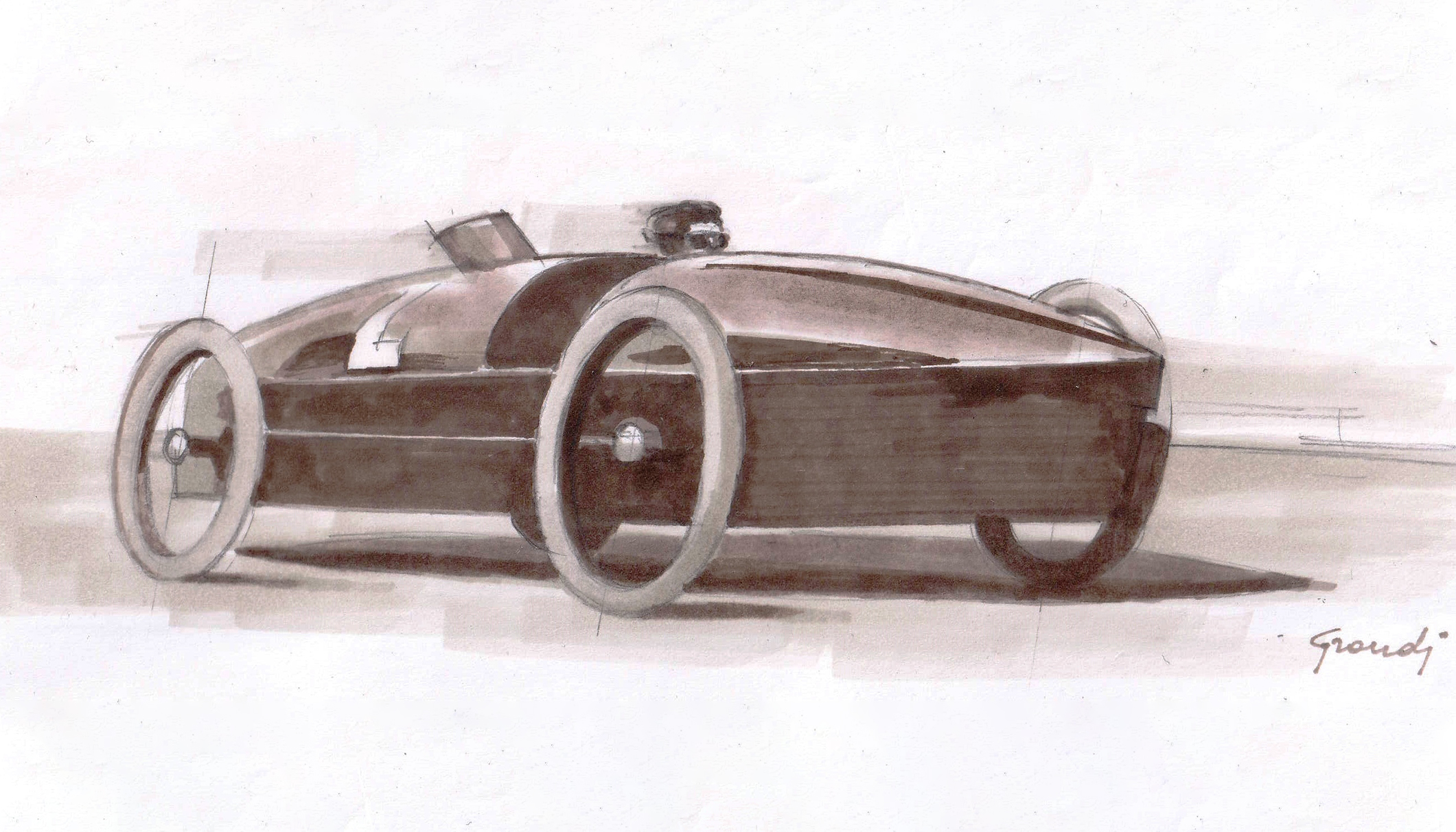

The idea of the Stanley brothers was to favour simplicity based on experience: the car was in fact made with wooden frame, just like the canoes of the time and covered with a perfectly stretched canvas. Efficient and lightweight. The engine, with its twin-cylinders and a capacity of 3,373cc, weighed just 84 kilos while the boiler and burner, which were powered by gasoline, weighed 270 kilos. The steam-formation boiler was patented by the Stanleys who produced and sold steam cars in the United States. Weighing less than 1,000 kilos the objective was reached immediately and would have been widely exceeded one year later, had a depression in the sand not caused the destruction of the car (thankfully not of its driver) during another attempt.

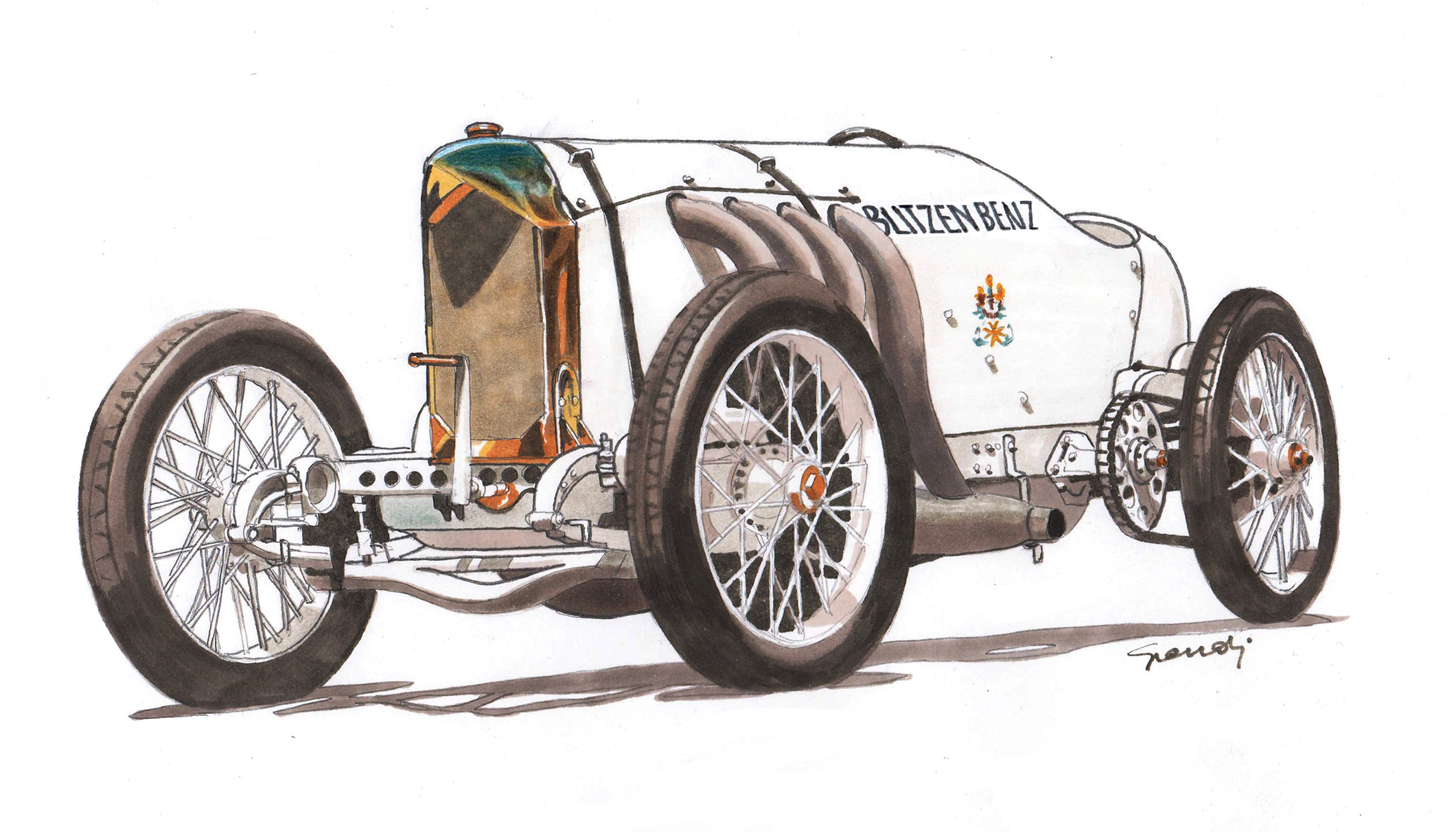

It took five years for a new milestone to arrive. This time it was Benz, still independent from Daimler and indeed competing with it, who decided to create a record-breaking car starting from one of his own racing cars. In comparison to the Stanley, the four-cylinder 21,504 cc engine, which weighed more than 400 kilos and produced 200 horsepower, pushed it to 228.096 Km/h. An increase of just over 20 kilometres per hour. Very little compared to the rapid progress of those years, however it was to be the last production-derived car to break the record. From then onwards, only specially-built vehicles would take on the challenge.

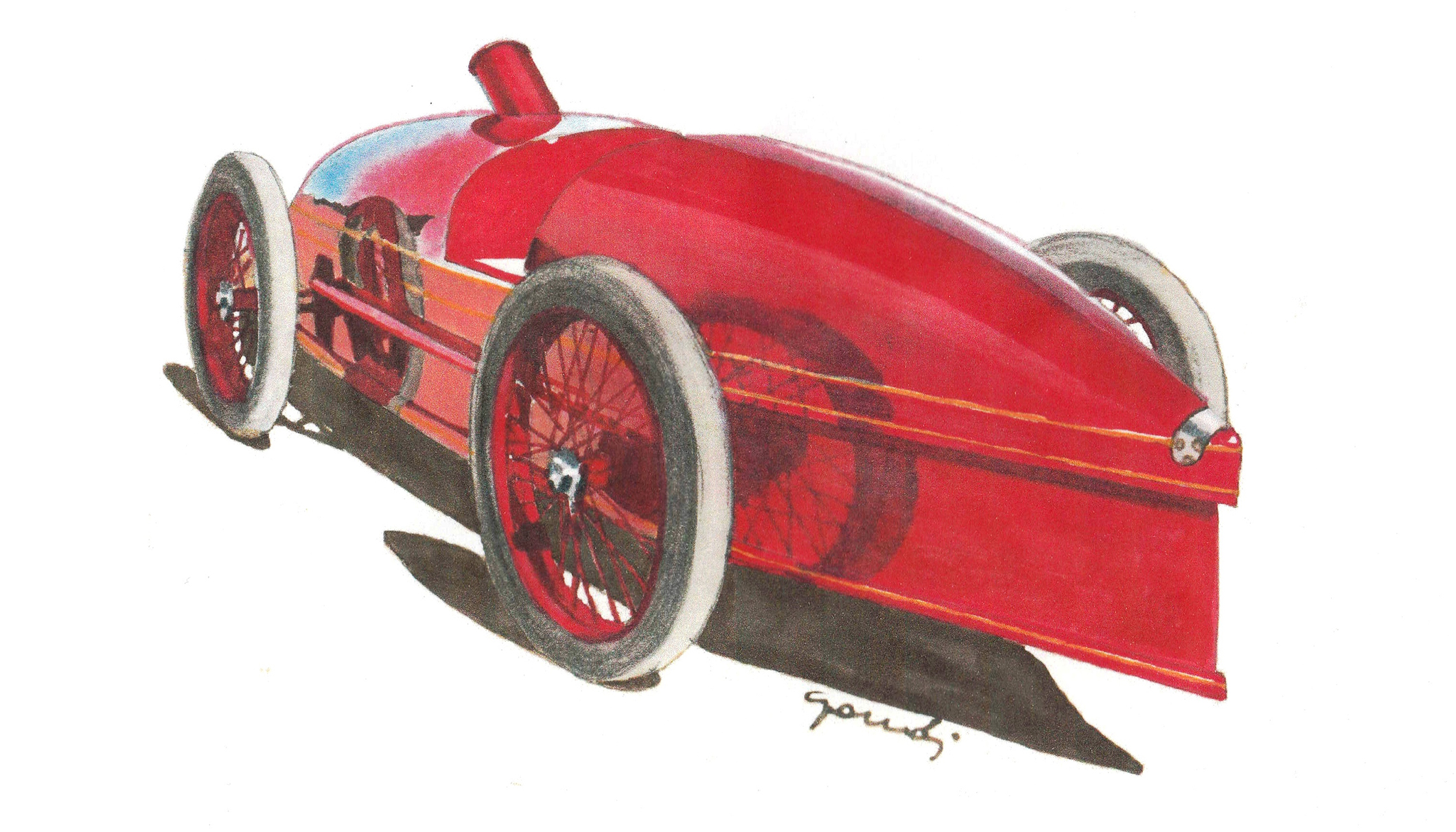

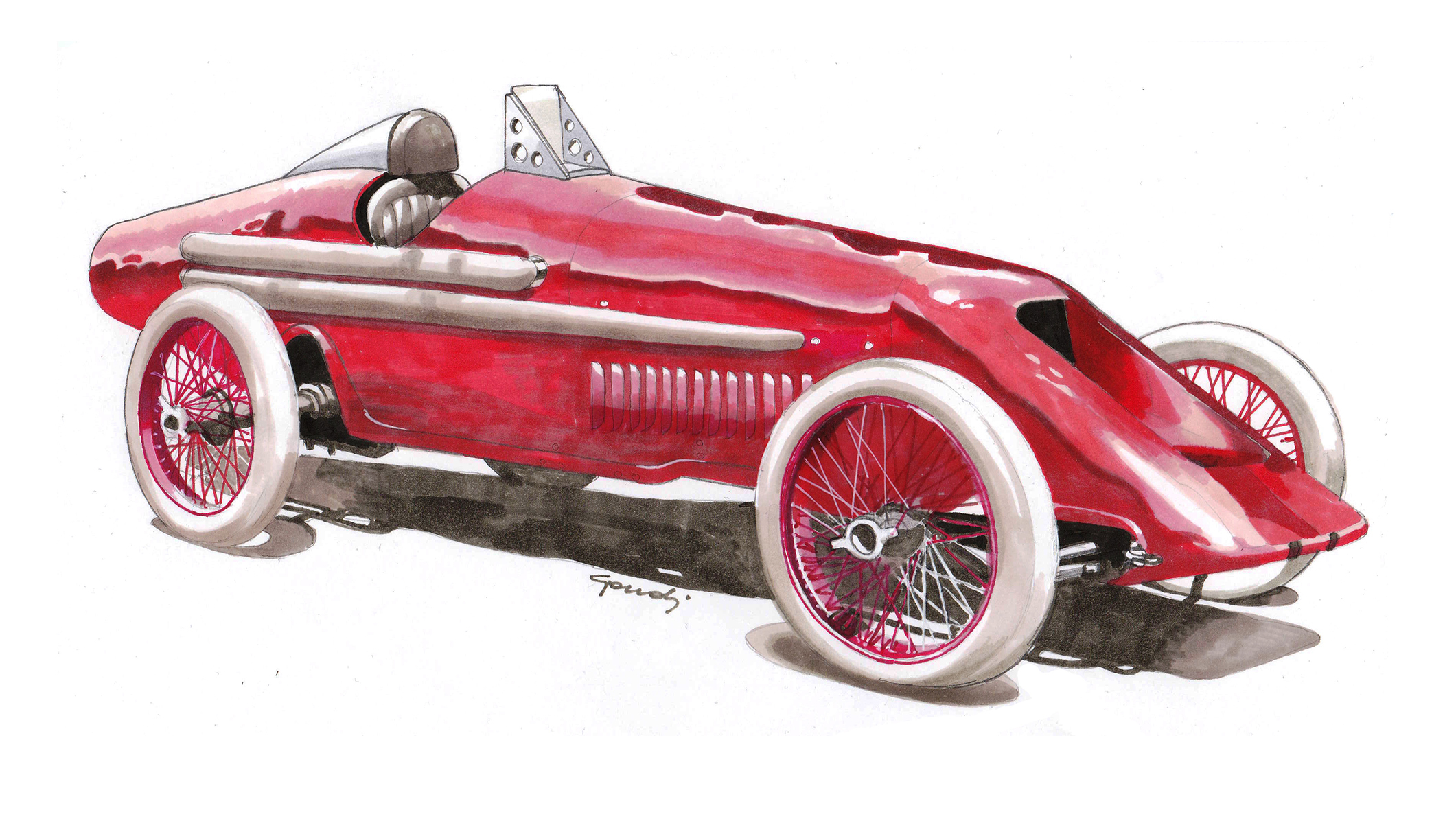

It was in April 1920 when the Duesenberg Double Duesy exceeded 250 kilometres per hour. Starting from a traditional chassis, the American car’s owner and driver, Tommy Milton, had two Duesenberg engines side-by-side that transmitted the torque through two parallel drive shafts joined by a special gear change that transmitted power to the wheels. The overall capacity of the engine was 10,000cc, which allowed it to produce 185 horsepower. A curiosity that sounds incredible but was often repeated at record-breaking attempts was that on various occasions there were no official timekeepers present and the registration of the record did not take place.

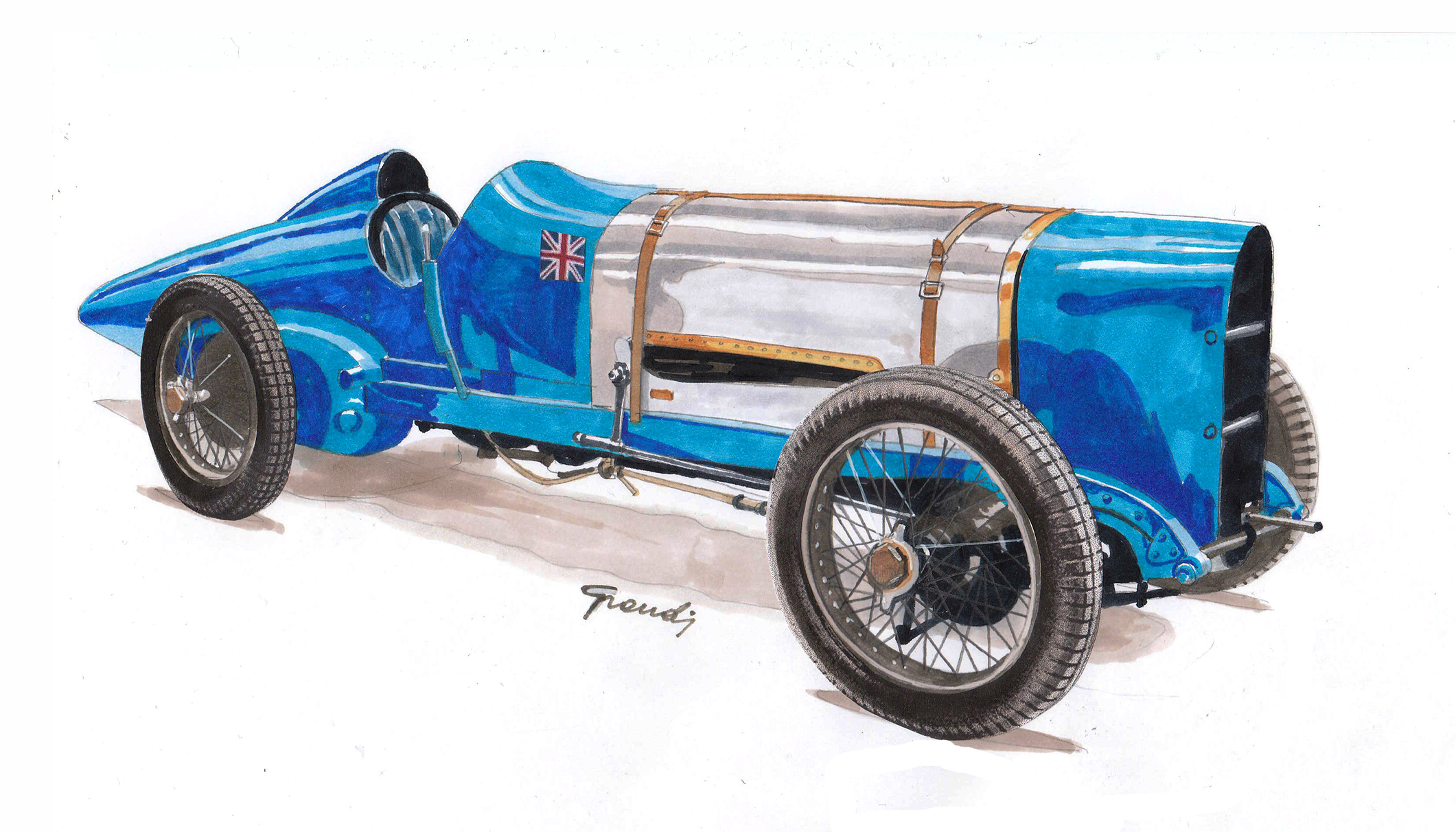

This is exactly what happened with this car. But the rich documentation produced guaranteed the new record that lasted until 1926. Speaking of homologations – this time the timekeepers were there, in July 1925 a famous surname from this discipline appeared centre stage: the Campbells. Father and son would go on to forever tie their names to the pursuit of speed on land and on water. In 1925 Malcom Campbell, with his first Bluebird built with Sumbeam, reached the speed of 242.750 km/h. But it wasn’t enough for him and he immediately started a new project that would raise that much further.

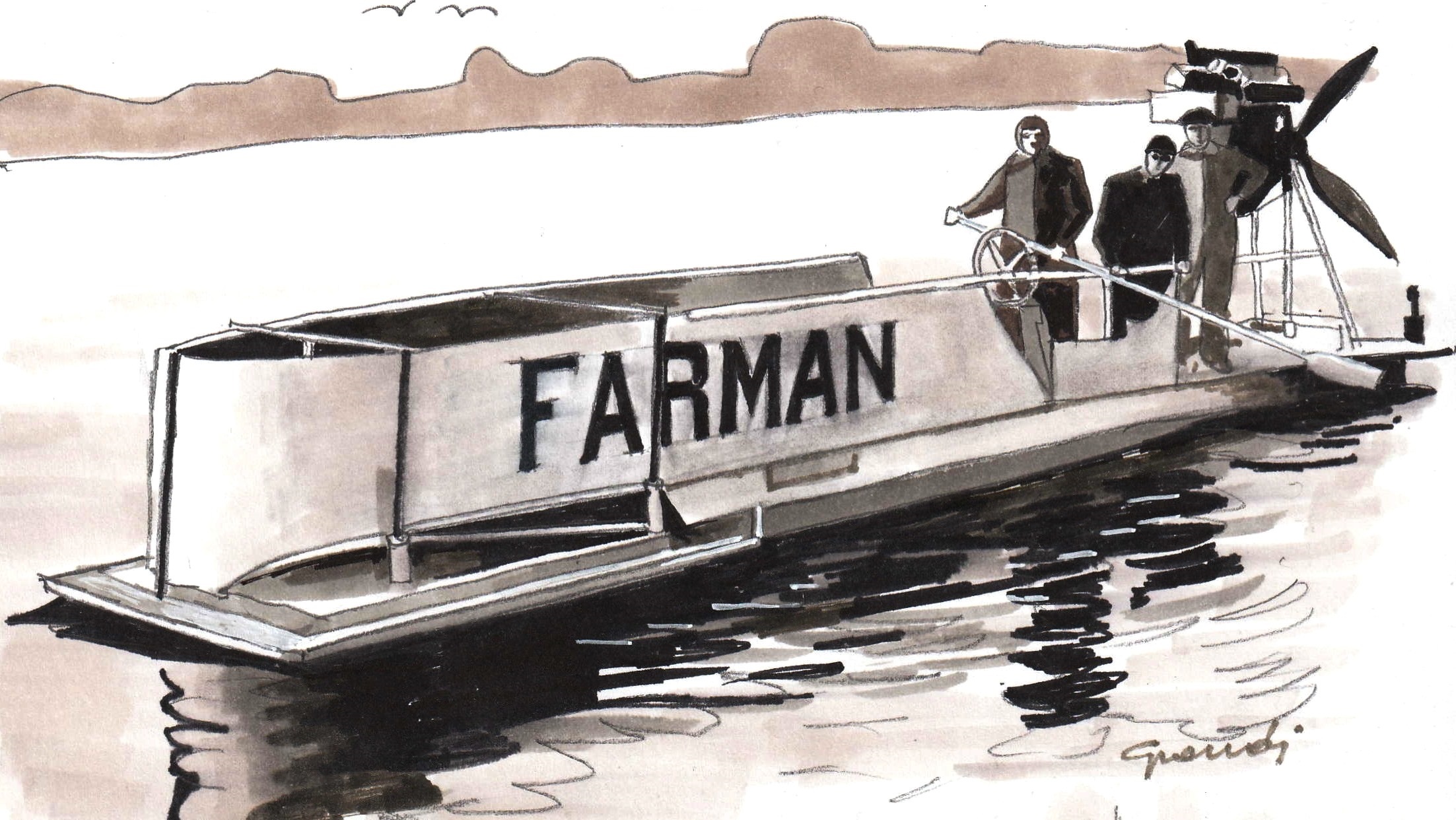

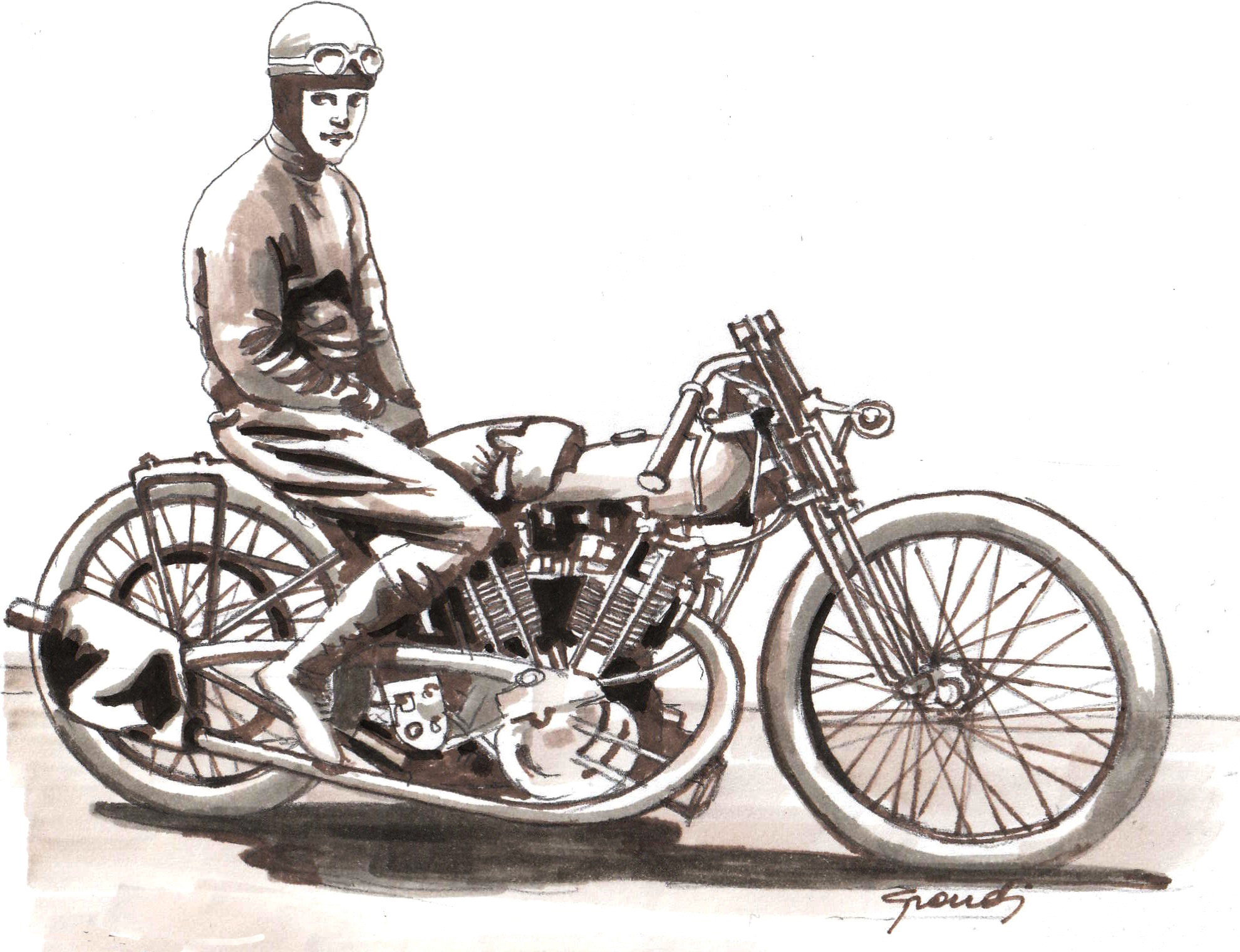

And what happened in the other worlds of speed in those years? Motorbikes grew steadily but remained quite far behind cars. In July 1924 the highest speed recorded in a record attempt in France was 191.50 km/h: The bike, a Brough Superior with an 867cc JAP engine, was nicknamed “the Rolls-Royce of motorcycles” for its extreme attention to detail. In the same year, speed attempts on water – began in 1911 – continued with a curious boat propelled by an airplane propellor engine, a sort of hovercraft that reached 140,664 km/h on the Seine.

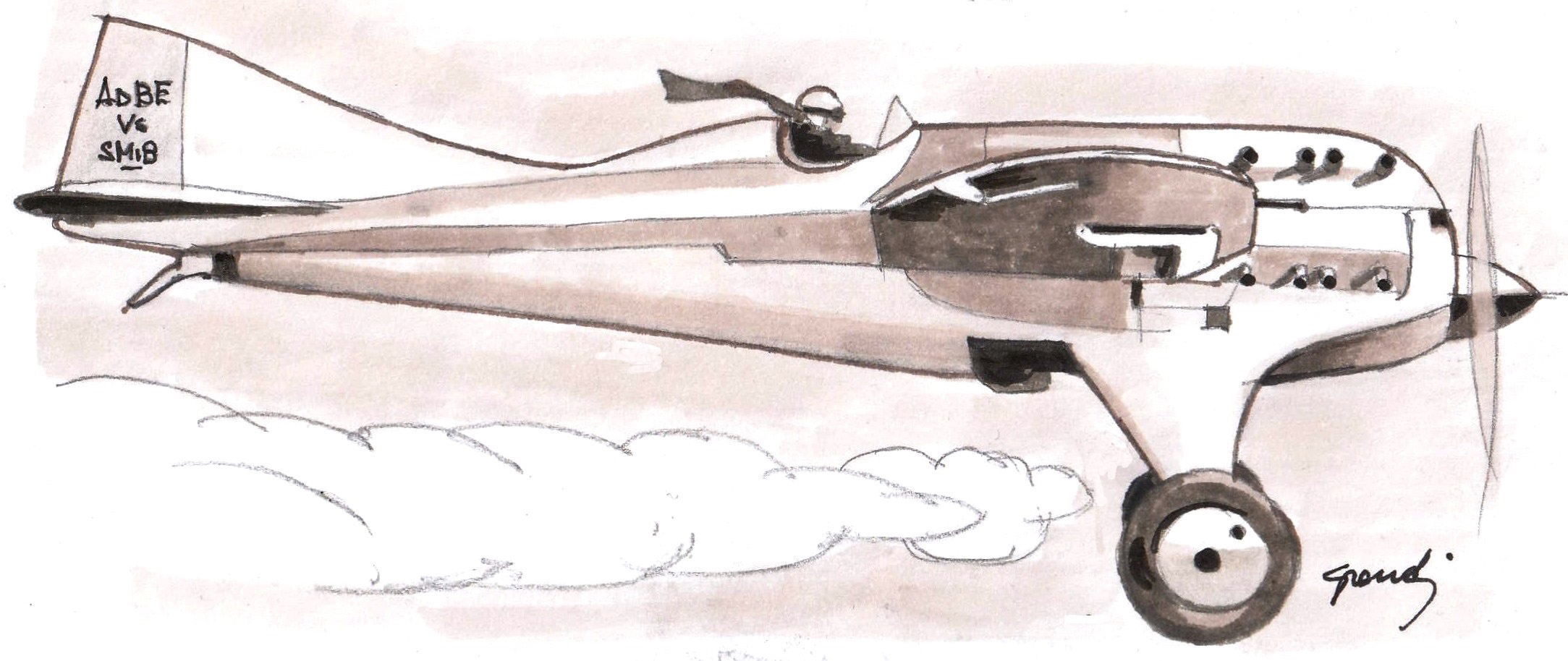

On another level entirely was the speed of progress of the aircraft, developed for use in battle during the First World War which, with the Bernard-Ferbois V.2 equipped with a single Hispano-Suiza W-12 engine producing 450hp, reached 448.171 km/h.