1951. Enzo “I killed my mother”

The win at Silverstone with Gonzalez and the 375 started the race for the World Title

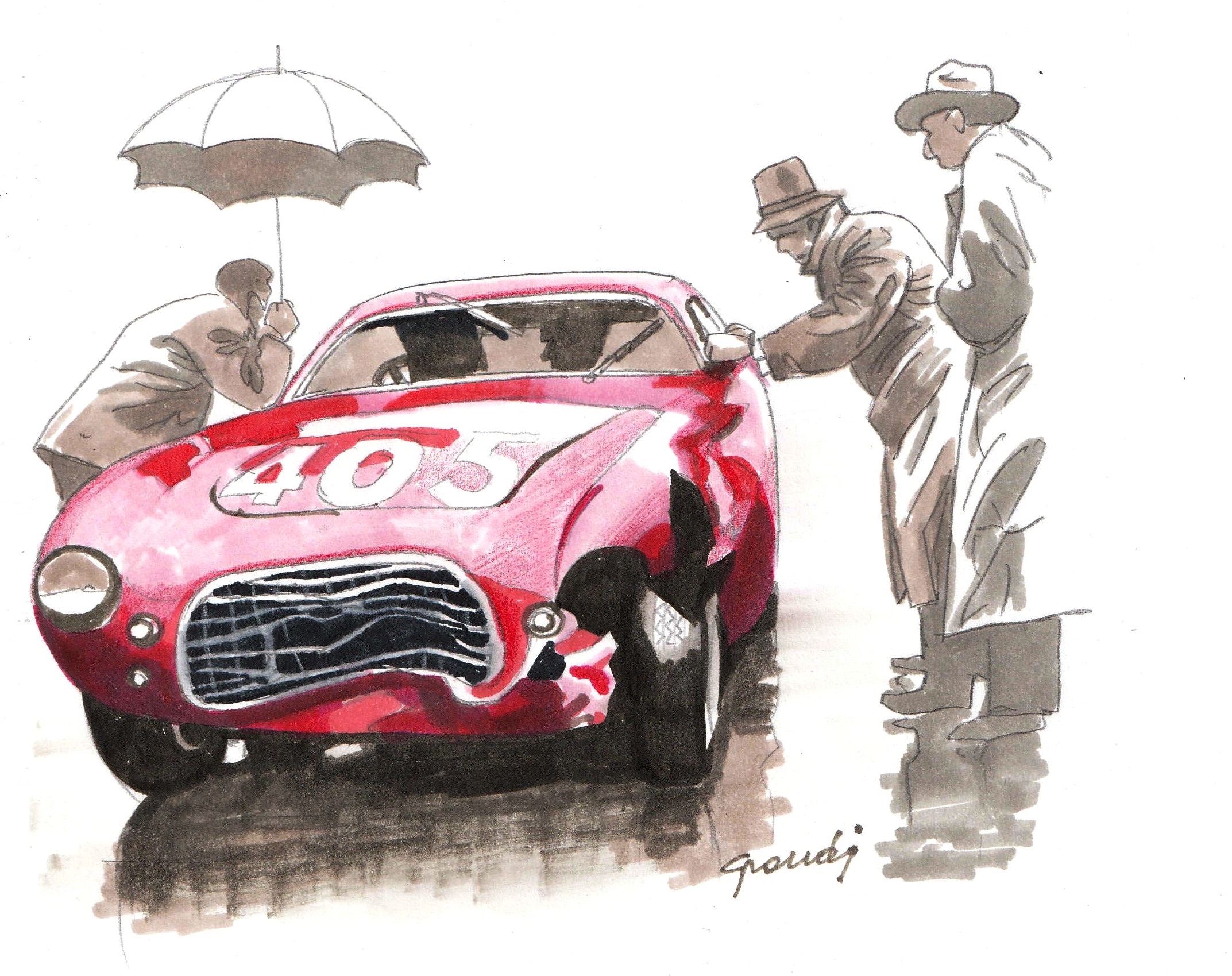

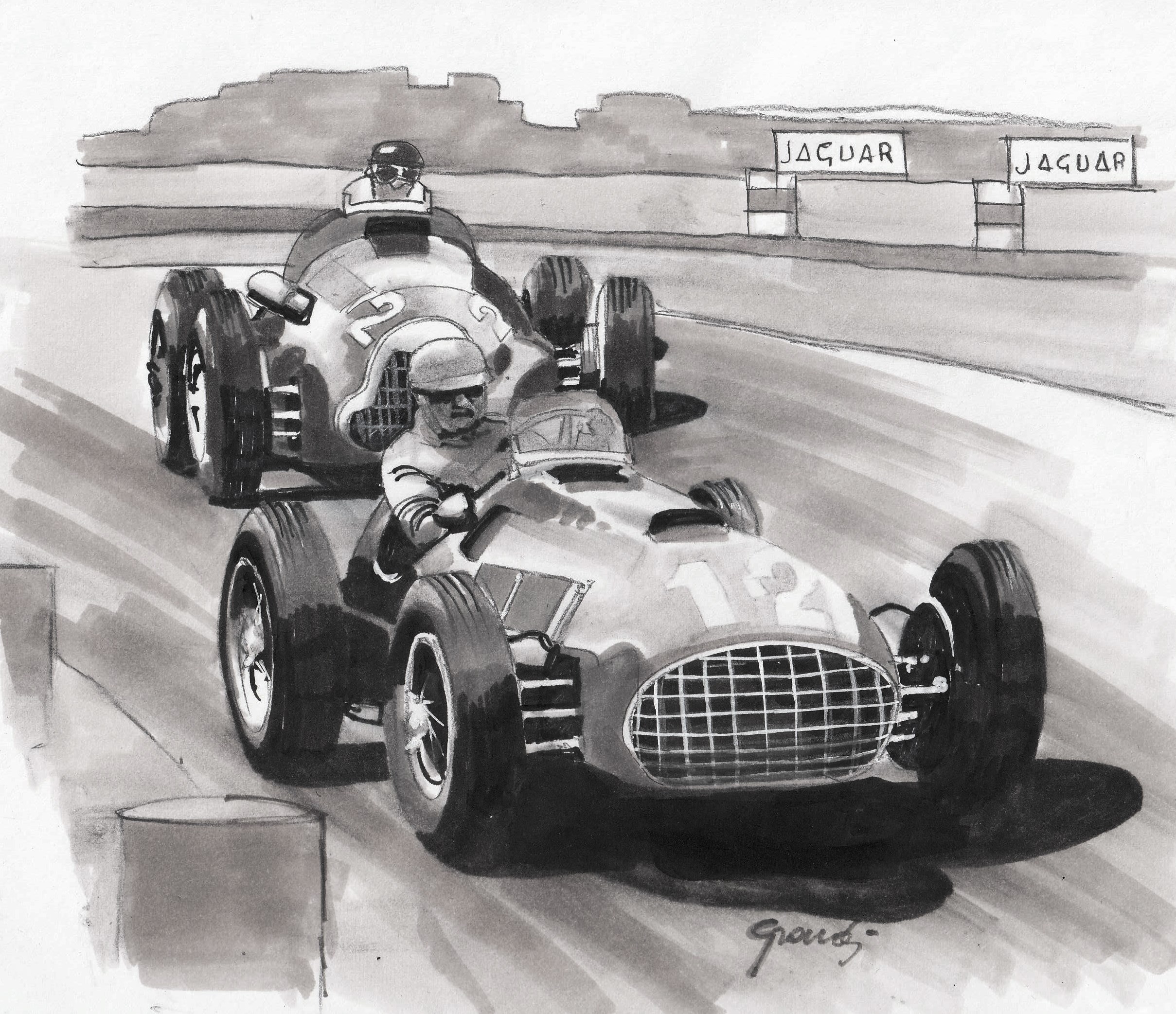

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

1950 was the year in which the International Automobile Federation launched the Formula 1 World Championship. Although the technical regulations have changed over time, this is the same championship that is still running to this day. The 1950 formula was based on two engines of the constructor’s choice: a supercharged 1,500cc engine (at that time there were no turbochargers driven by exhaust gases and the compressors driven by the engine itself were used which, fatally, in addition to adding horses also subtracted a few), or normally-aspirated engines with a capacity of 4,500cc.

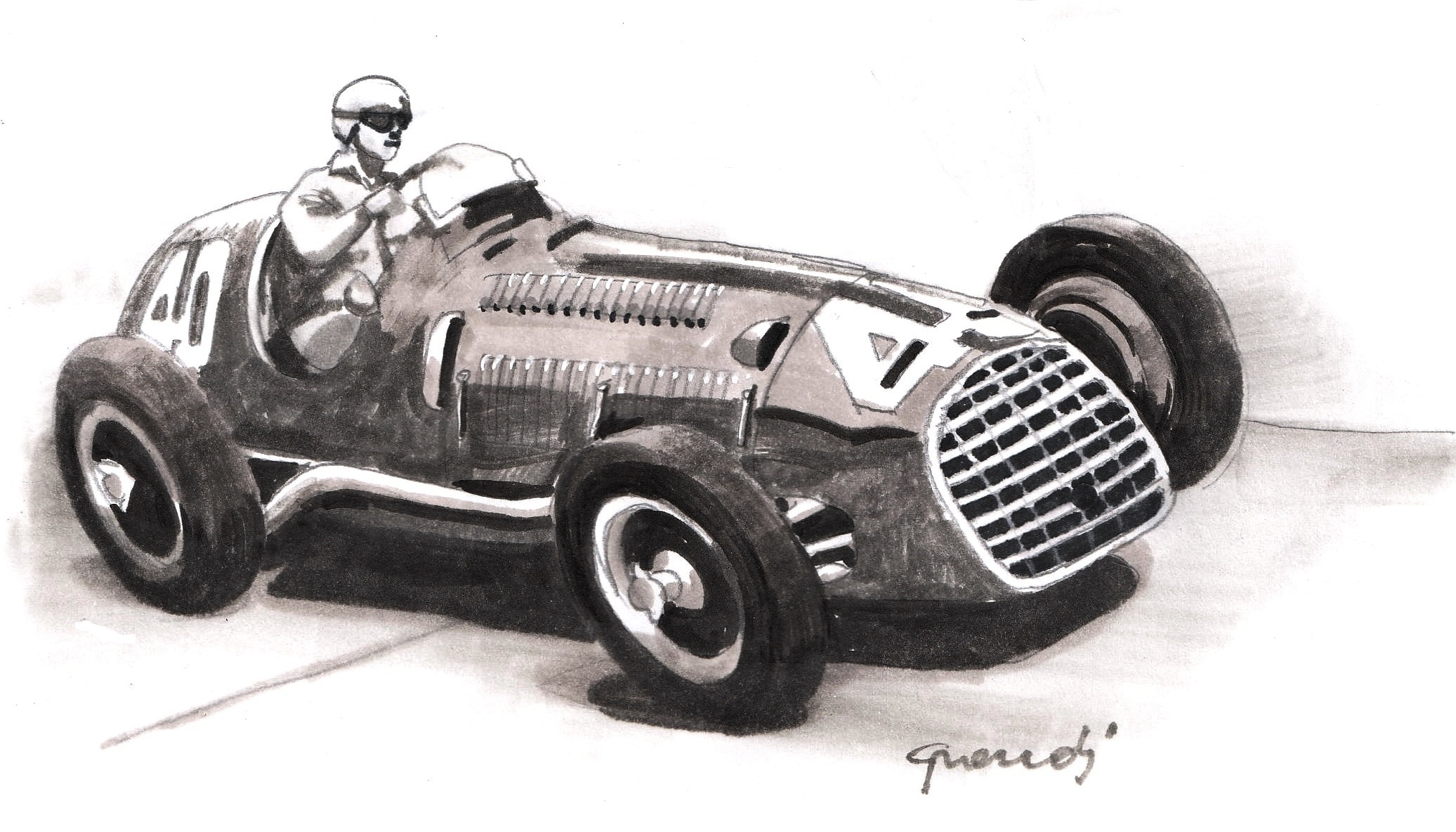

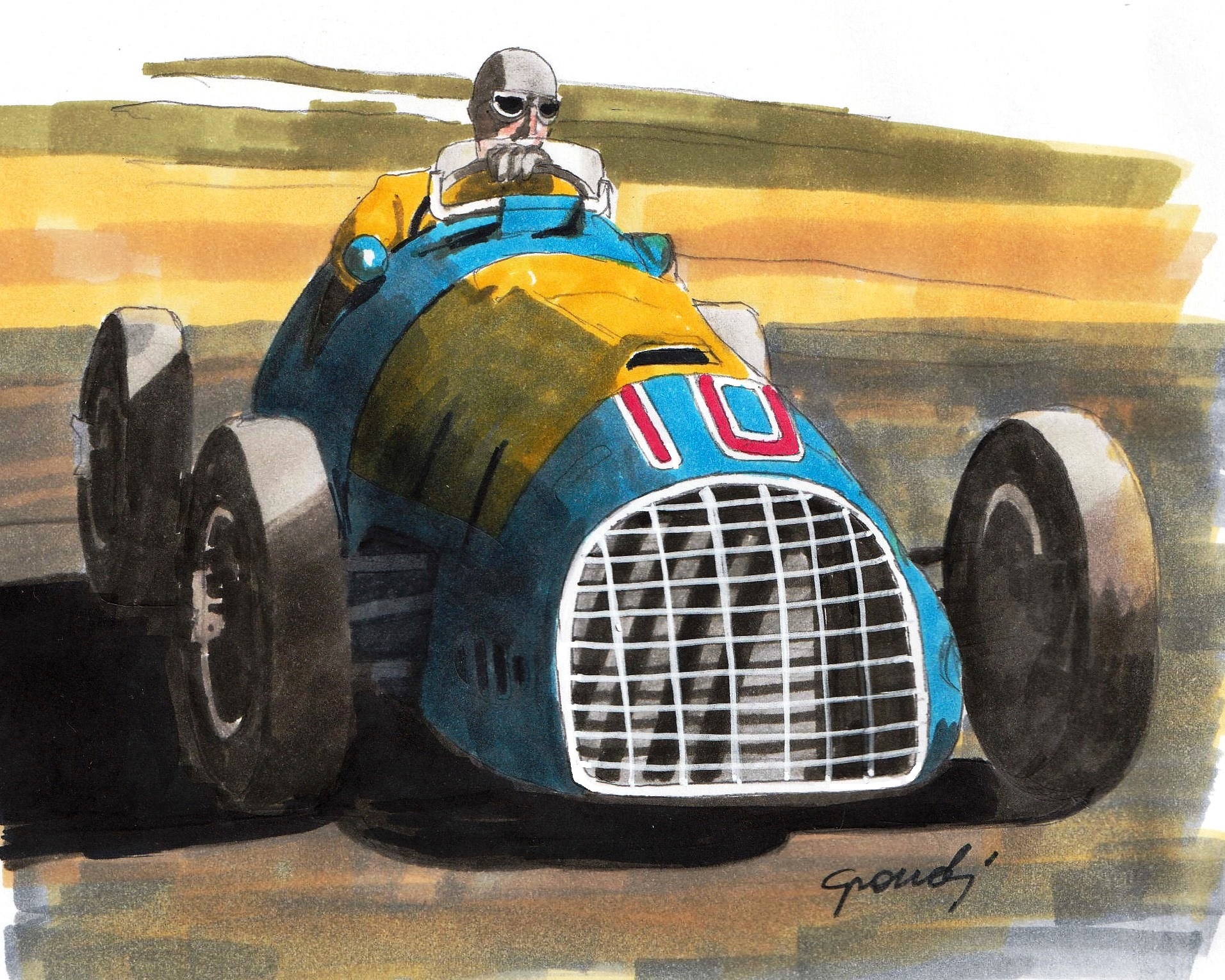

Ferrari realized that any attempt to develop his V12 engine, designed in 1946 for the 125S, despite being supercharged, would not have allowed him to beat the Alfetta 158. This car, born in Modena in 1938 on the premises of Scuderia Ferrari, had so much performance it was still unbeatable. While Ferrari’s engine was already getting on a bit, the 158, now renamed 159 after some updates, was very old – 12 years old no less – and yet it was still winning races.

But we all know what Alfa Romeo meant for Ferrari. A deep love that turned into bitter rivalry and a desire for revenge after Enzo was excluded from the team’s sport projects in 1939.

Aware of the technical inferiority of his single-seater cars, Ferrari did not send his cars to Silverstone, to the debut race that was easily won by Alfa. However, he did enter the following two GPs at Monte Carlo and Bern, confirming that the unfortunate 125 F1, despite being further modified with dual overhead camshafts and a two-stage Roots-type supercharger, was incapable of producing the high-end power required to compete with the strong eight-cylinder Alfa Romeo 158.

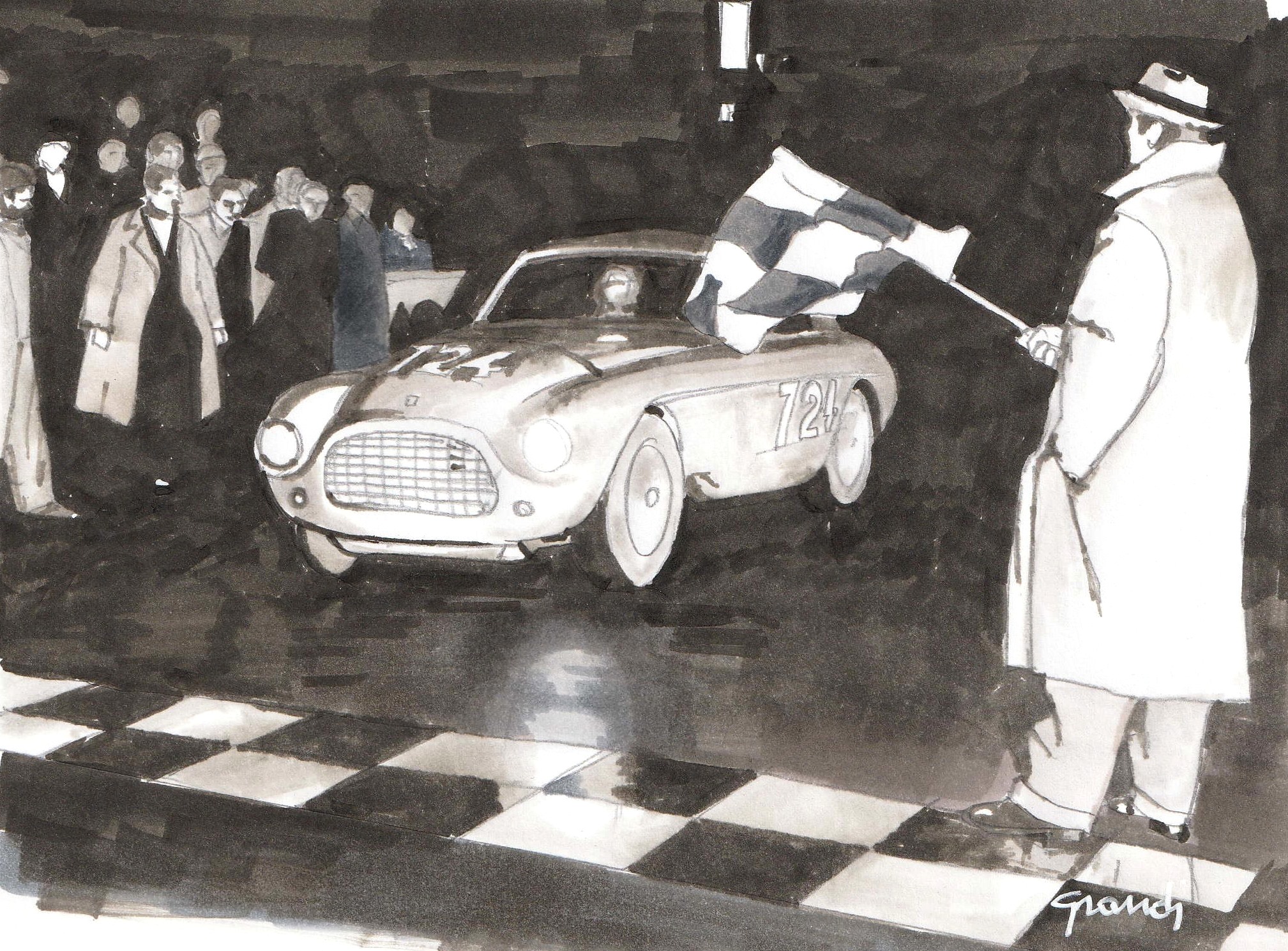

For Ferrari, defeat was unacceptable. It was not enough for him to have won the 1000 Miglia for the third consecutive time with one of his finest and wealthiest clients, the young Count Giannino Marzotto; he was not satisfied with the successes in many countries across the world after Chinetti’s win at Le Mans. He wanted to win in Formula 1. And he wasn’t prepared to wait too long either.

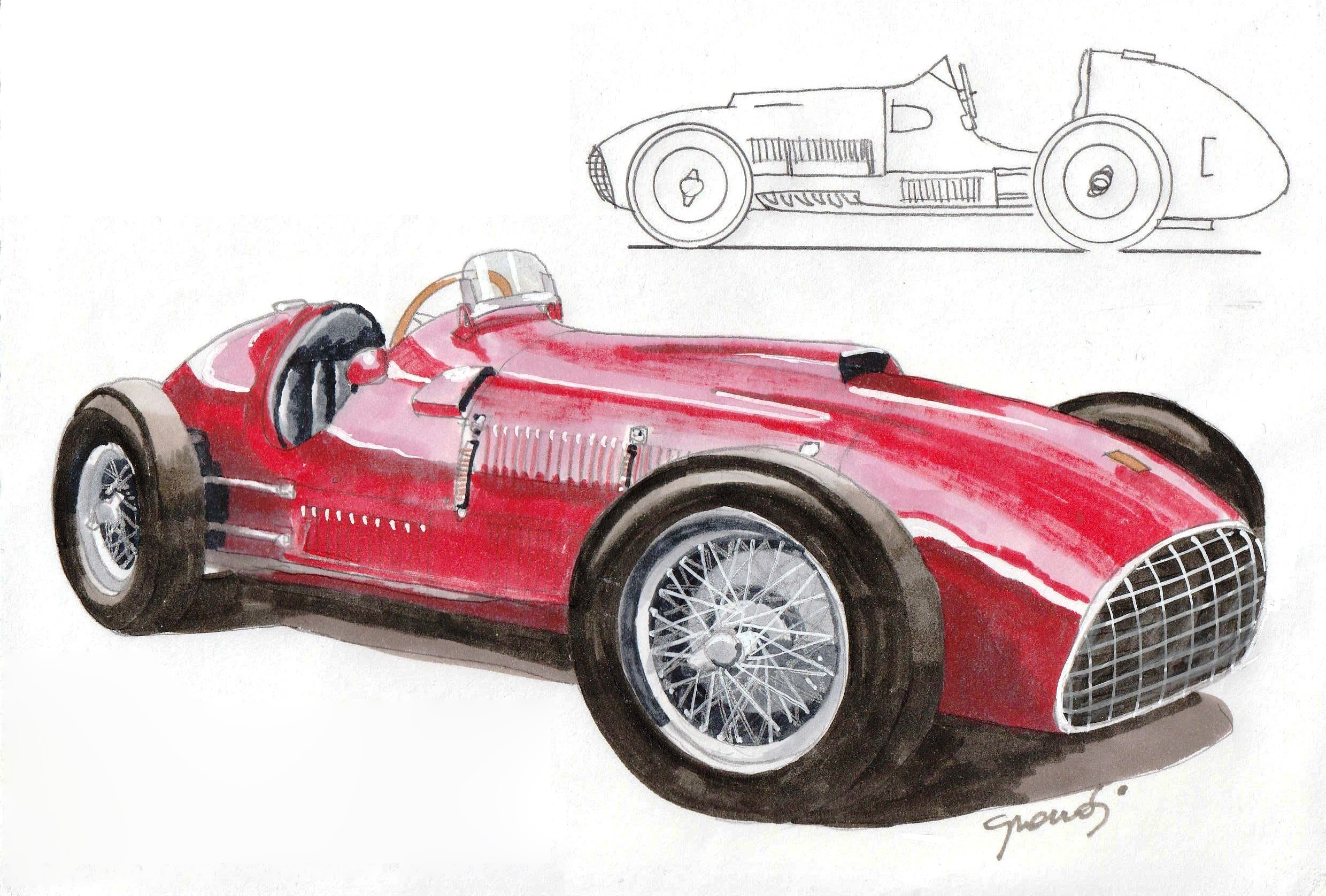

As a man who loved fine mechanics, the charm of the 4,500 cc V12 engine that the engineer Lampredi had proposed to him the year before, won him over. Lampredi had played the right card: the aspirated engine consumed less, meaning it would only need to stop once for refuelling instead of twice for the Alfa. Work commenced but did not progress quickly. In addition, changes to the regulations planned for the 1952 season would have limited its use to less than two years. An investment that in many respects was a wasteful one. Infuriated by the team’s performance, Ferrari demanded that the new V12 be brought to the race as it was. The capacity was growing slowly and the only available one was just 3,300 cc. Too few for Ascari who took it to the Belgian Grand Prix and finished far behind the Alfas that were dominating the World Championship with Fangio and Farina at the wheel.

For all his life, Ferrari loved Monza: among the many reasons for this love, without question the precious breath of fresh air he had received after the Italian Grand Prix in 1950. Finally the engine had grown to 4,500cc and Ascari, after scoring the second-fastest time during the practice session, had also taken the lead in the race, ahead of Fangio. In the end, he landed a welcome second place on the podium after running into mechanical troubles which meant he had to abandon his Ferrari and climb on board Serafini’s (driver changes were allowed back then). Ferrari’s ascent was becoming increasingly evident and fuel consumption, as expected, was lower than those of his rivals.

With Alfa Romeo’s victory with Nino Farina in the first World Championship behind him, the signs for 1951 were positive: in the Argentine storm of January, a driver destined to write his name indelibly in the history of Ferrari won both races with a 166 in the Formula Libre. At the 1000 Miglia, the success was repeated for the fourth time thanks to Villoresi. There was only one thing that weighed on Enzo’s heart: the health of his son Dino, now clearly on the path towards a tragic destiny. Muscular dystrophy proceeded relentlessly and the person Enzo had dreamed about becoming his brilliant heir, inexorably began to abandon him.

The first signs of Ferrari’s reprisal were clear from the very first GP in Switzerland, where the naturally-aspirated Ferrari 4500 of Taruffi finished behind Fangio but in front of the World Champion Farina. Also in Spa and France, came a double podium: Ascari was second and Villoresi third and again, in Reims, Ascari second with Gonzalez third who had taken advantage of the lower consumption of the 375.

It was now clear that Alfa Romeo had themselves a very problematic rival. On 14th July 1951, the British GP was held at Silverstone. The very fast circuit, originally a military airport, was very different from today’s track. At the time, cars managed to record lap averages above 160 miles per hour. González took pole position in his 375 (375×12 = 4500…), and the start with Fangio and Farina next to him in Alfas, announced what was to be an arduous fight: González and Fangio alternated first position throughout the race, but González finally took the lead after a breath-taking pass at the famous Becketts curve and defeated Fangio by over a minute, after he was forced to stop to refuel.

Using one of his famous phrases left in the annuals of history, Ferrari, learning of his first victory and of Alfa’s defeat, said “Today I killed my mother”. This was a measure of just how profound his relationship was with Alfa Romeo.

From that moment, Ferrari’s growth was unstoppable. There were three races to go until the end of the Championship. Ascari won with the 375 at the Nürburgring and Monza. The World Title was within their grasp when Enzo, unexpectedly, refused to use the new 18-inch Pirelli tyres at the final GP, in Spain. He insisted on using the usual 16-inch wheels that he knew and trusted. Alfa Romeo switched and Fangio snatched the title that until that moment had seemed lost.

Just as he was a cautious driver through fear of a fatal accident, Enzo was also cautious in accepting novelties. This was clearly demonstrated a few years later when the British introduced their rear engines and he stubbornly defended his layout with yet another phrase, at a time when tractors had long since taken the place of the oxen: “The horses pull the cart, not push it”. That’s why the engines should always be in the front… No one has ever analysed the impact of Ferrari’s resistance towards innovation. But, knowing his story, we can say that it would certainly be a positive one.

Speaking of big decisions.. Enzo had decided to race in Indianapolis the following year… see you for the next instalment.