The turning point. Ferrari takes advantage of the German offensive to prepare to become a constructor

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

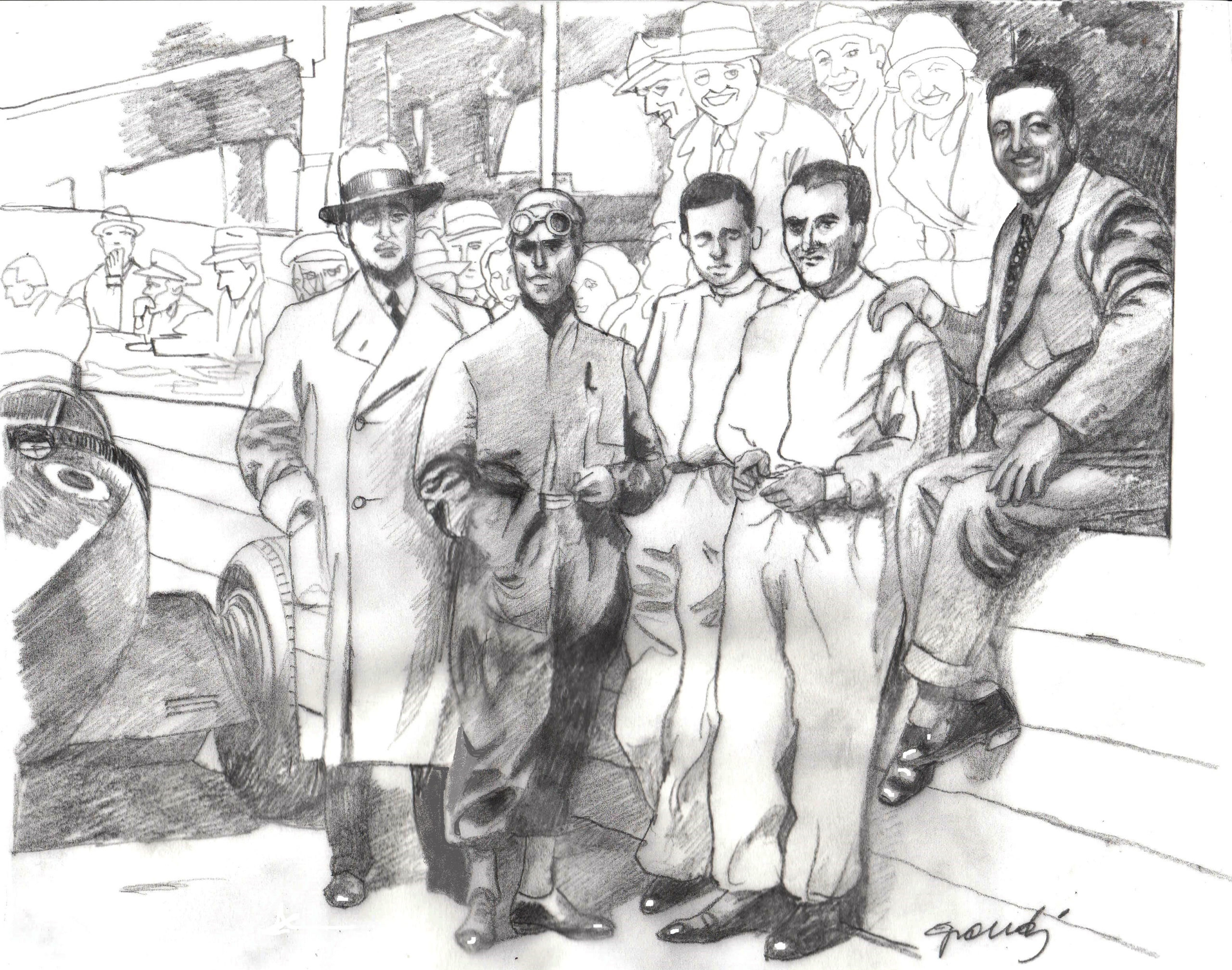

Legend has it that Tazio Nuvolari, on the eve of the 1935 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring where his antiquated P3 was due to contend with nine official Mercedes and Auto Union, asked whether the Italian flag had been prepared for the podium. Apparently, the officials looked at him with a mixture of incredulity and sympathy. And yet Nuvolari knew, as only the greats can, that he could do pull this off and, the next day, he brought home one of the most beautiful victories of all for Scuderia Ferrari and Alfa Romeo.

Up until that moment, however, the road had been anything but a smooth one for Enzo: after the many successes together at the beginning of the decade, Nuvolari tried to extend his power by asking that the name of Scuderia Ferrari become Scuderia Ferrari – Nuvolari. Although he was only too aware of the importance of the driver at a time when Alfa Romeo were not at the peak of their performance, Enzo denied his request and their relationship collapsed. The Ferrari name had to remain unique! In 1933, Alfa Romeo withdrew from racing and entrusted Ferrari with the activity through the Scuderia, but did not provide him with P3s which remained silent in Milan. Ferrari attempted to overcome this shortcoming with the engagement and victories of Achille Varzi that allowed the Scuderia to remain competitive. For his part, Nuvolari, after racing with Maserati, was unable to join the Auto Union team, and only re-joined the team two years for the 1935 season.

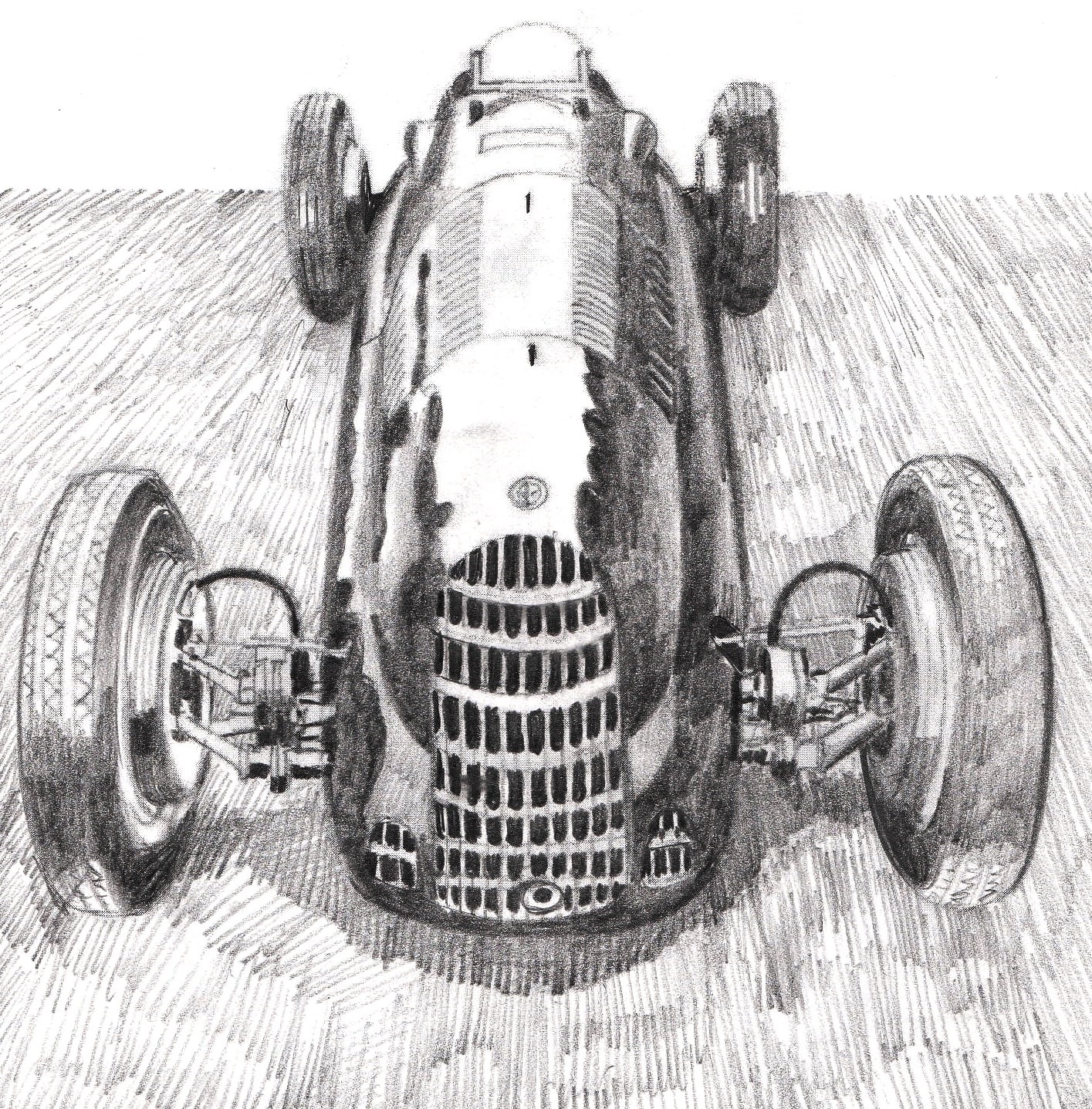

This sporting scenario, it must be remembered, was set against the backdrop of a power struggle between two the totalitarian states of Germany and Italy (which were not yet allies). The Germans had made motoring one of their national symbols. Italy had to respond. Alfa Romeo, which by then had been nationalized, finally made all the materials at its disposal available but the gap between Ferrari and the Germans was immense. Despite winning at Nürburgring, thanks to the talent of Nuvolari and the fact that many of the German cars had retired due to mechanical problems, Ferrari knew he had to develop a weapon of his own that could defend itself against the competition which used engines with much higher displacements: Mercedes had a 5,660cc engine that over the years reached 575 hp while Auto Union deployed a 6,000cc one that was good for 520 hp. The P3 had arrived at 3,800cc with a power output of 265hp – although it did weigh just 680kg, 70 less than its opponents – which wasn’t enough to give it a sufficient advantage on the faster circuits. The Germans had made the most of the 750Kg maximum weight regulations for Grand Prix cars, using larger and more powerful but heavier engines. Alfa had worked on keeping weight to a minimum but it was an uneven fight.

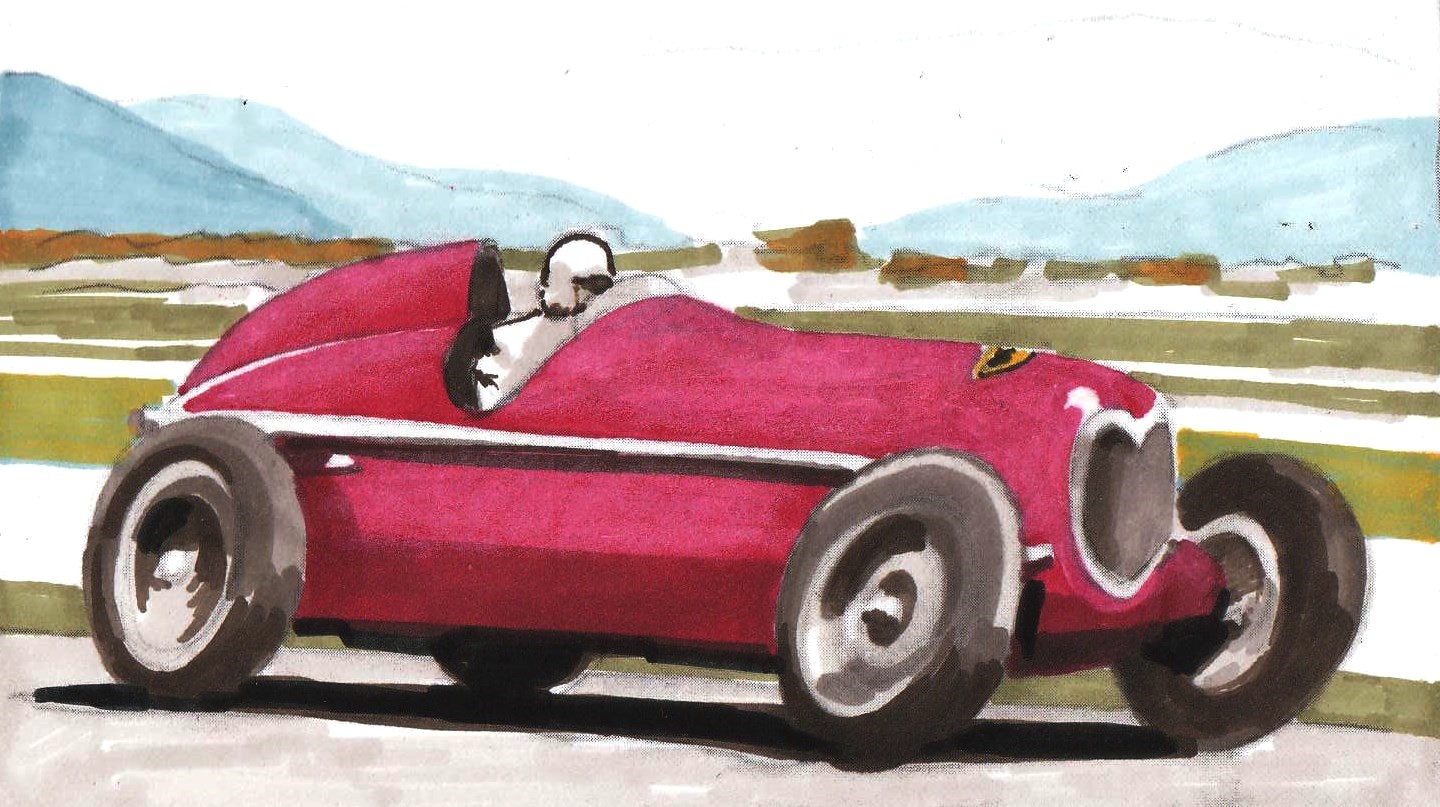

Italian creativity, combined with his burning ambition to make his first racing car in Modena, led Ferrari to accept an idea from his loyal designer Luigi Bazzi: to install a second, rear-mounted engine and to compete at the races with a twin-engine car. It sounds incredible today, but the car was designed and built in just three months, in Modena, at the Headquarters of the Scuderia in Viale Trento Trieste. The year was 1935 and the car was phenomenally quick, so much so that Nuvolari was able to beat both the kilometre and the mile speed records with it, reaching a staggering 323 km/h. But it was also problematic: it was difficult to drive on twisty circuits and it had an enormous appetite for tyres, which struggled to transfer all that power to the ground.

Aware of the impossibility of defending himself against the German platoon, Ferrari focused on the new “voiturette” formula that featured supercharged cars with a maximum displacement of 1,500cc. With the support of a man destined to play an important role in the future of Enzo the Constructor, Gioachino Colombo, he commissioned and built the 158 in Modena, at the Headquarters of the Scuderia.

The performance was such that it brought the Formula 1 world titles of 1950 and 1951 home to Alfa Romeo. That’s right, 12 years after his debut! Alas, in those years voiturette races were successful but were, fatally, secondary to the Grand Prix cars. Always focused on bringing prestige to Italy, Enzo managed to enter his Alfas in the Vanderbilt Cup in New York in the autumn of 1936, winning with Nuvolari and covering Italian newspapers with triumphant titles as a result.

All this was not enough, however, as politics had now taken over, and Alfa Romeo, which in the late 1930s produced more aircraft engines than cars, was put in the position to return to the racetracks. In December 1937, after eight years of activity and 144 victories, Ferrari closed the Scuderia. Alfa offered him a very lucrative three-year contract which however took away the absolute power that he loved and used to perfection. All of this sparked his desire to become an independent constructor. We’ll see how in next week’s instalment.