Bimotore and 158. Enzo: making a virtue out of need. The Scuderia became a manufacturer to try to stop the mighty Germans

With the valuable support, depth of knowledge and illustrative talent of Prof. Massimo Grandi

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

Grand Prix car regulations set a minimum car weight to ensure excessive lightening doesn’t compromise safety. It’s no easy task to comprehend the regulations from the 1930s where the required weight of 750 Kg was also the maximum. That’s right, the maximum.

In those conditions, with the freedom to use engines of any displacement and power, the tendency was to make lighter cars and allocate the remaining available weight to the engine that had to be as powerful and prodigious as possible.

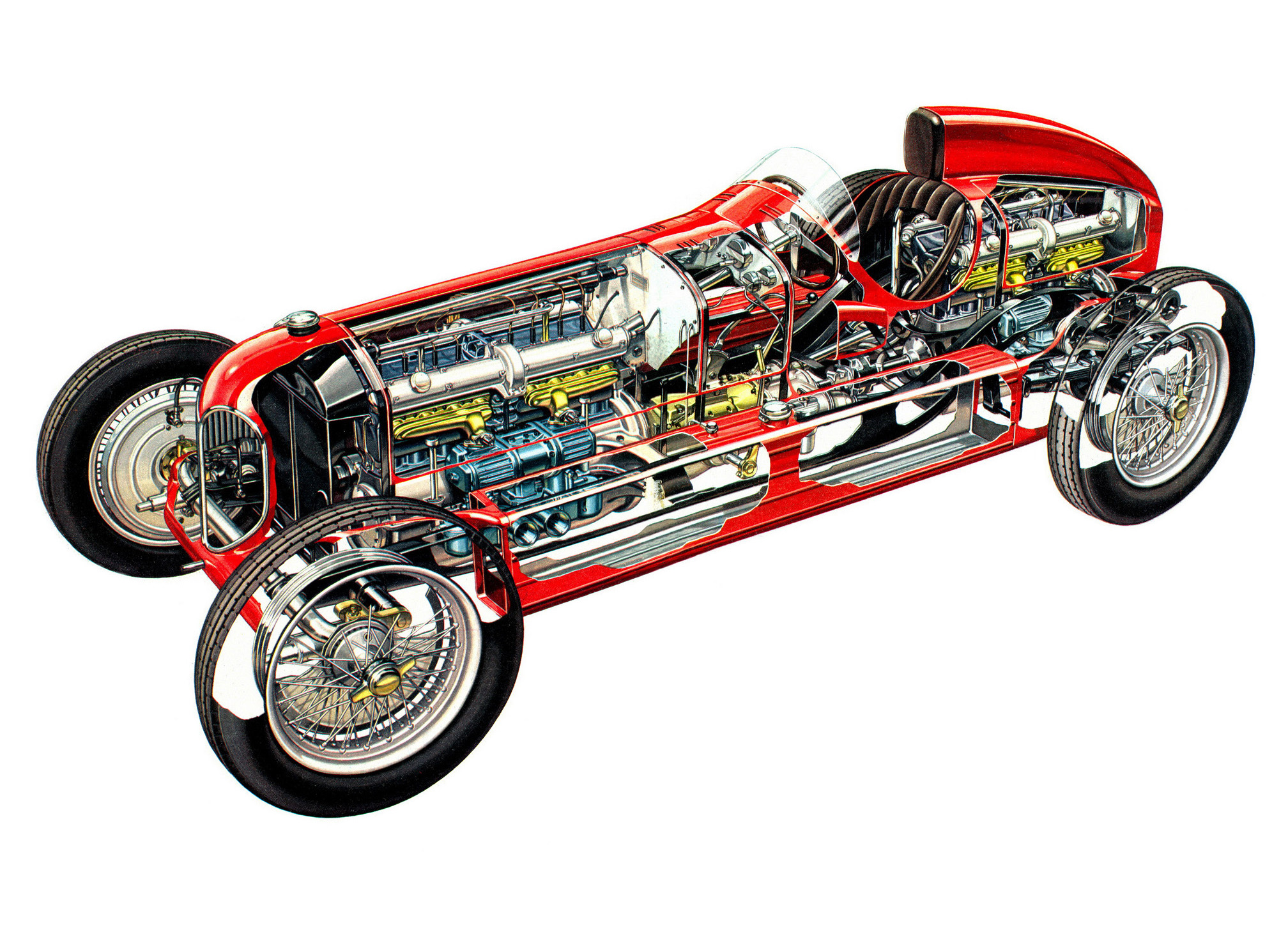

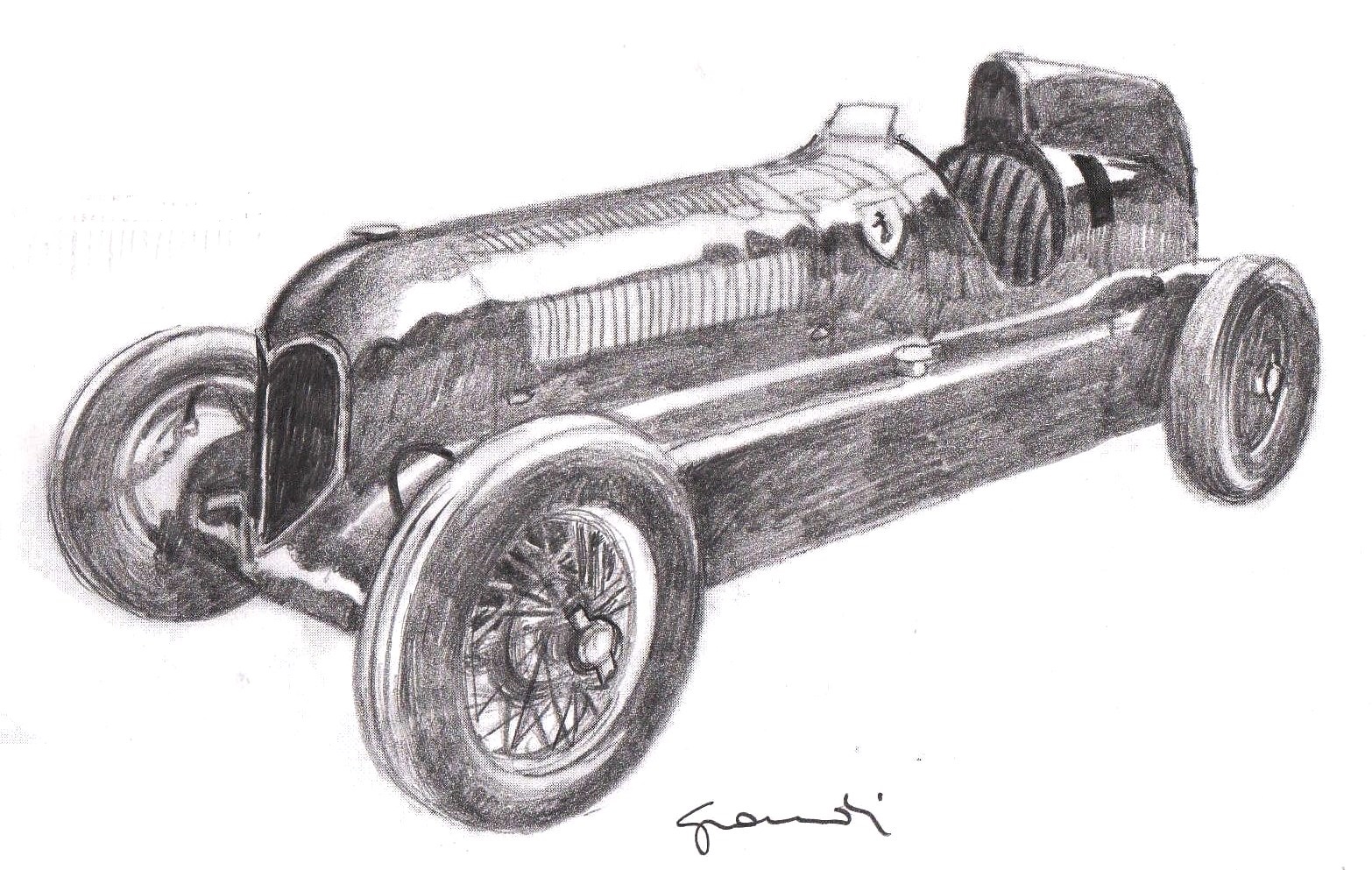

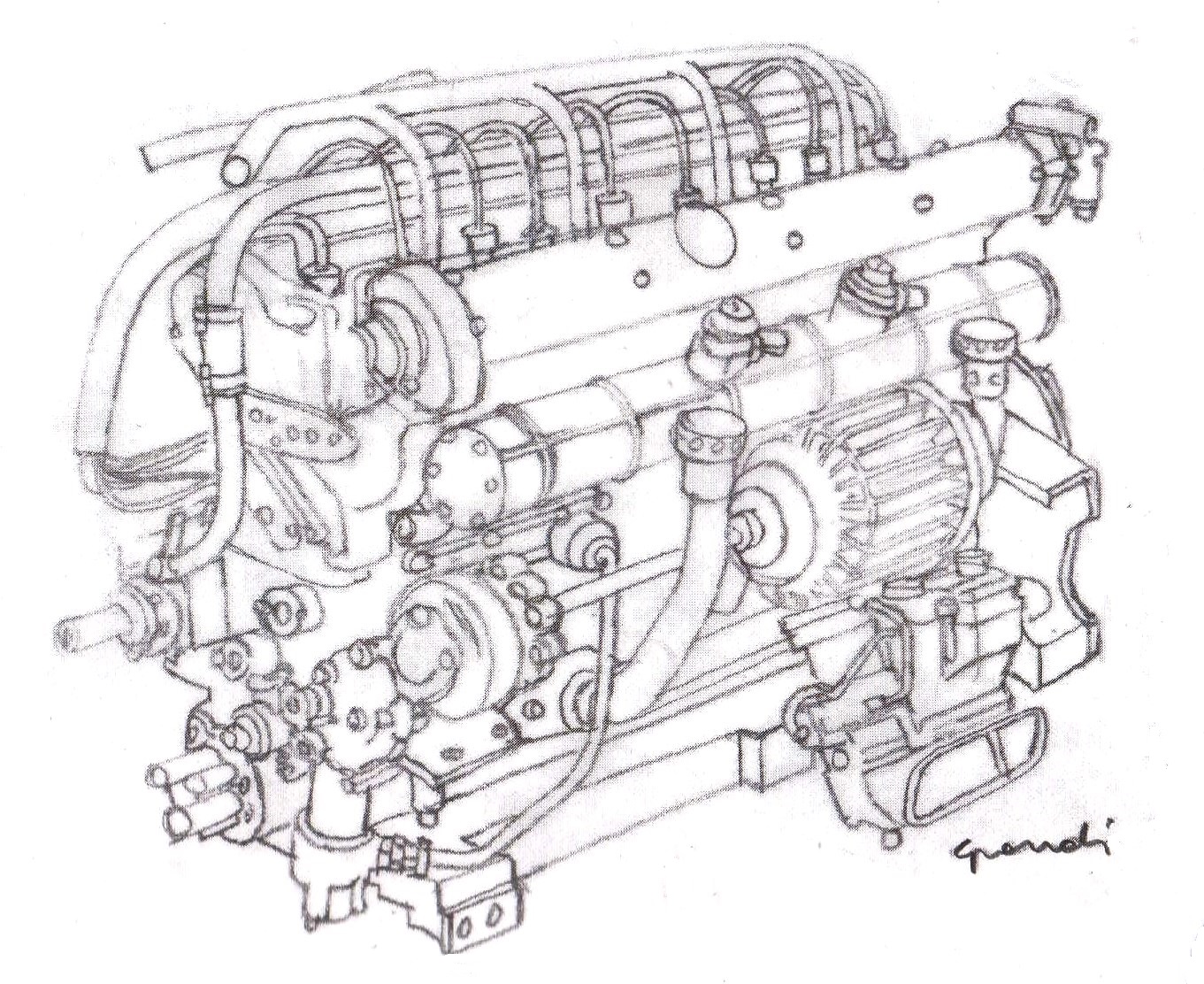

The 750 Kg formula came into force in 1934, when Vittorio Jano’s Alfa P3 was at the peak of its performance. But this was a car designed for the older regulations with a heavy steel frame and a refined 8-cylinder in-line supercharged engine capable of producing “just” 215 horsepower.

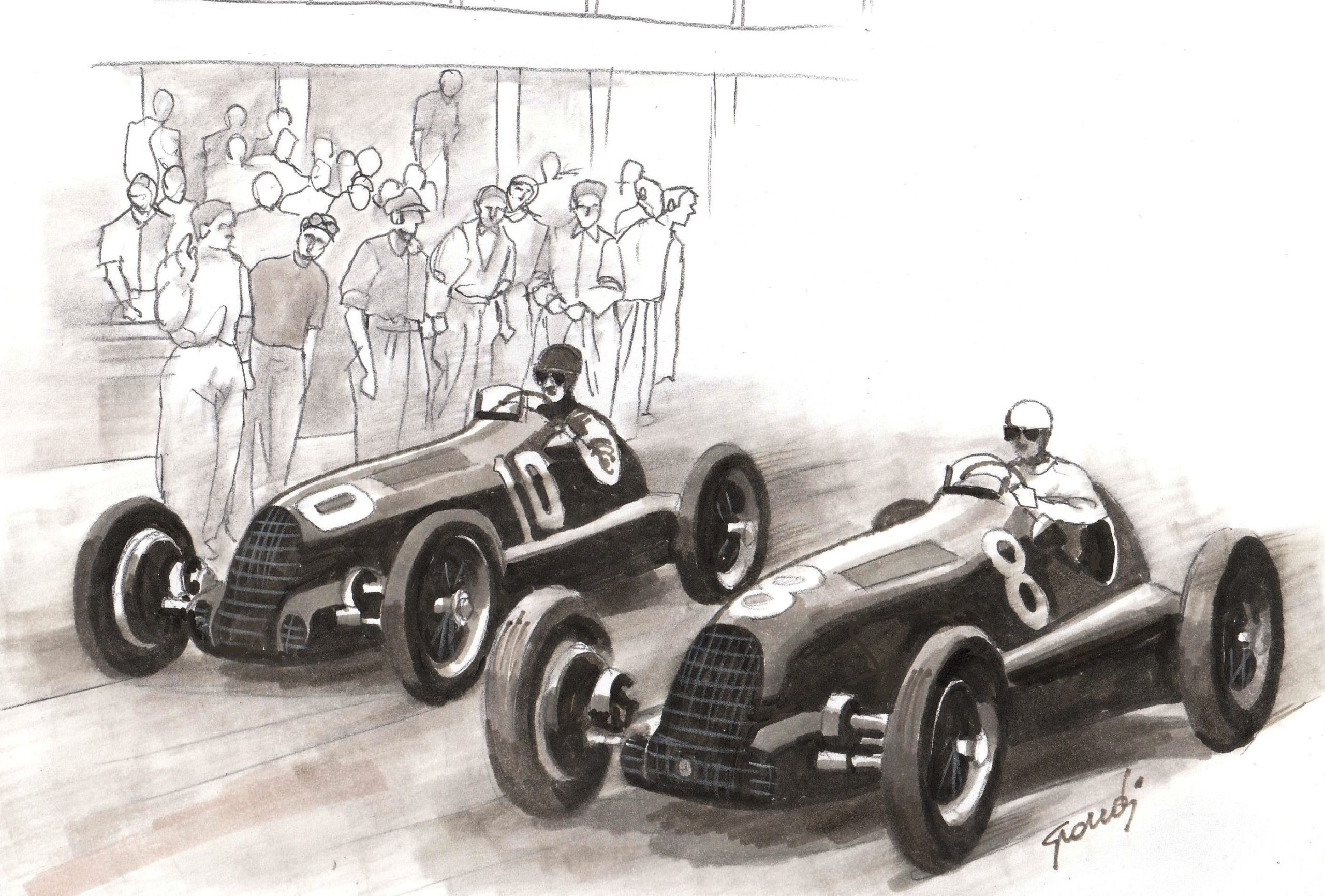

Despite being agile, reliable and fast, the P3 was immediately outclassed by the different interpretation of the regulations of the German manufacturers, Mercedes and Auto Union, who reaped the benefits of having designed their cars from scratch for the 750 Kg formula using light alloys for the chassis – both weighed less than 50 Kg – and, something that should not be ignored, from the fact that both received important subsidies from the new National Socialist regime that had sensed the propaganda potential of Grand Prix racing. It should not be forgotten that Germany had been humiliated and economically crippled after suffering defeat in the First World War, and the German politicians leveraged their newfound nationalist pride.

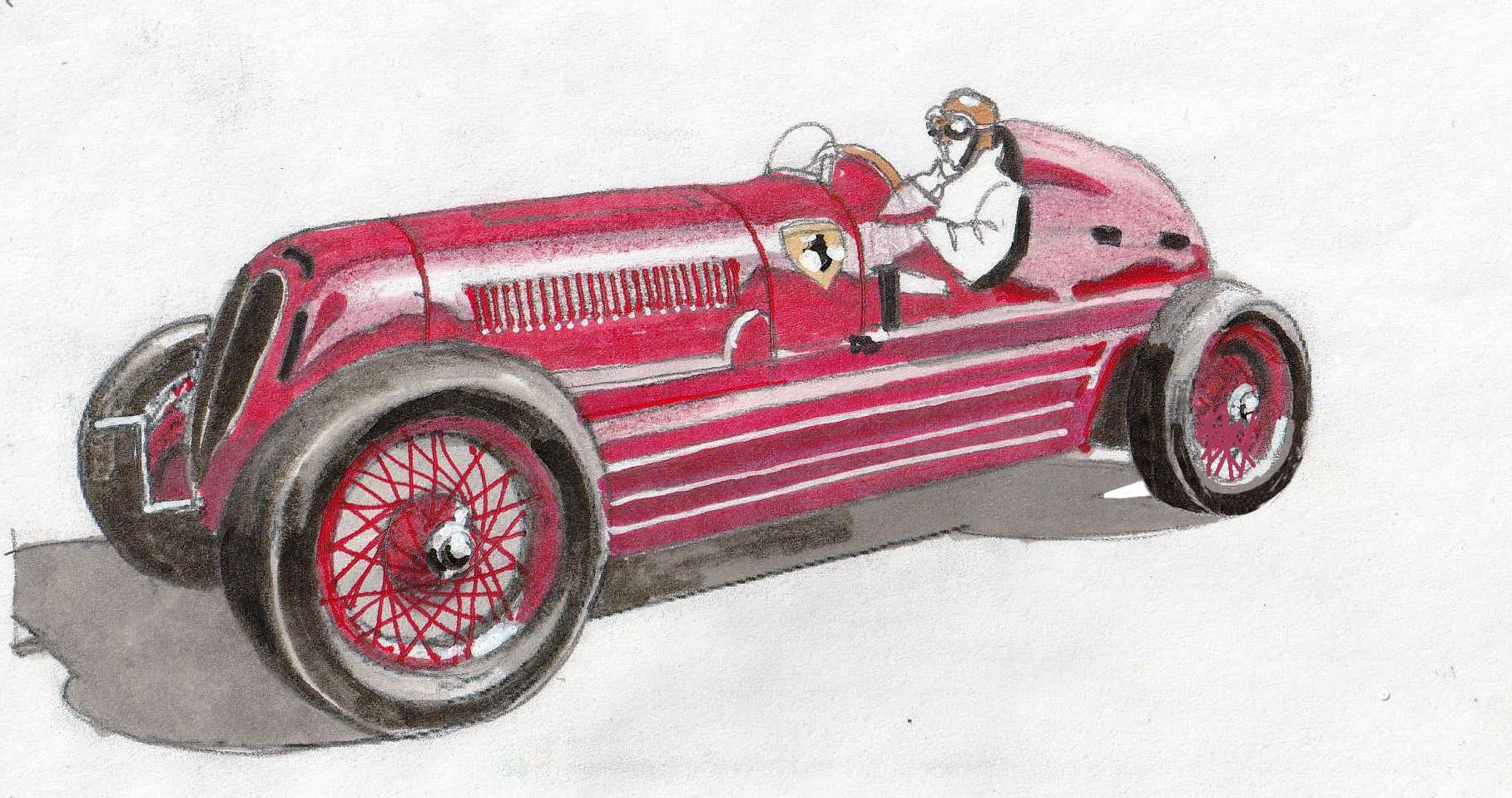

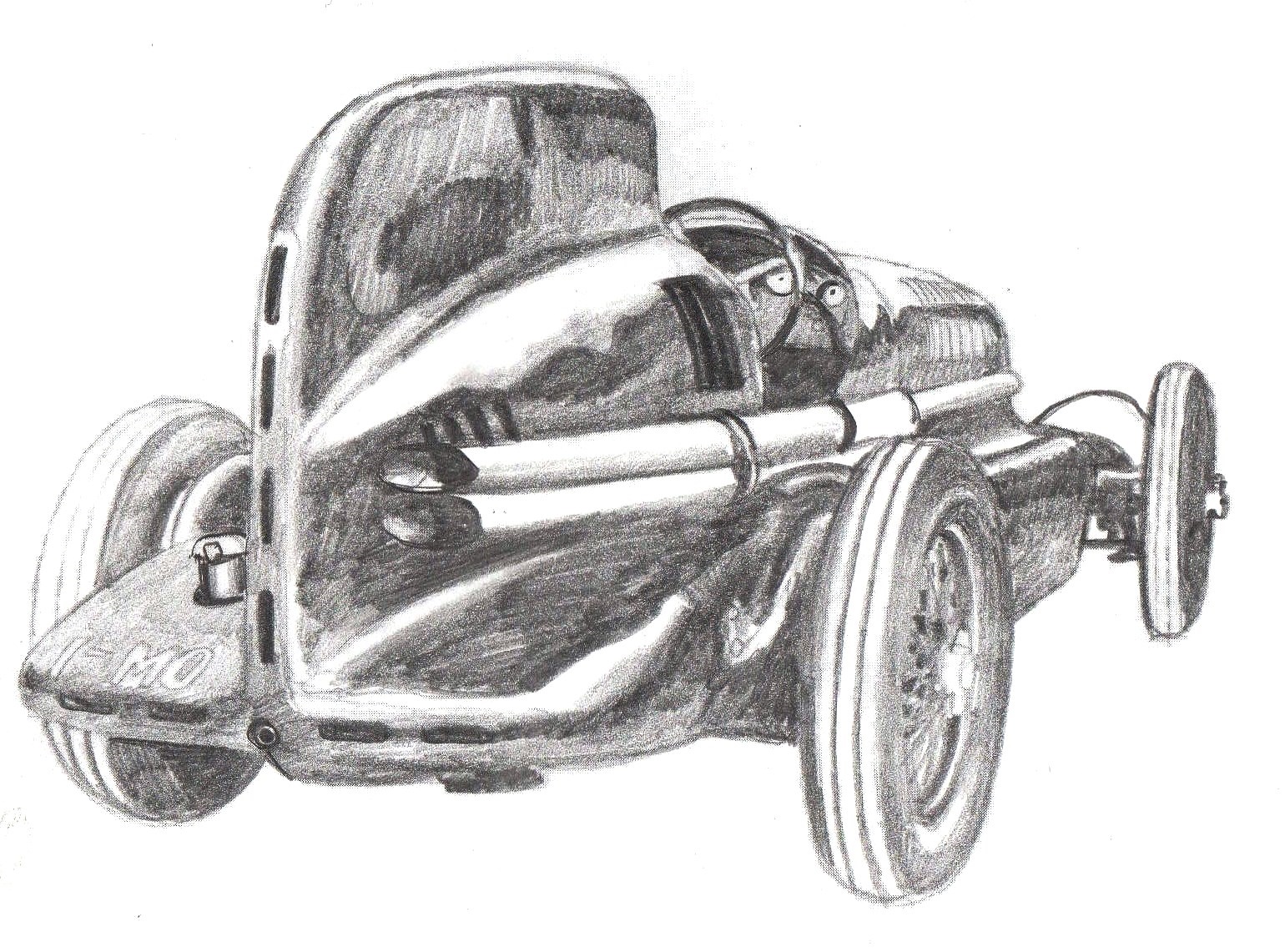

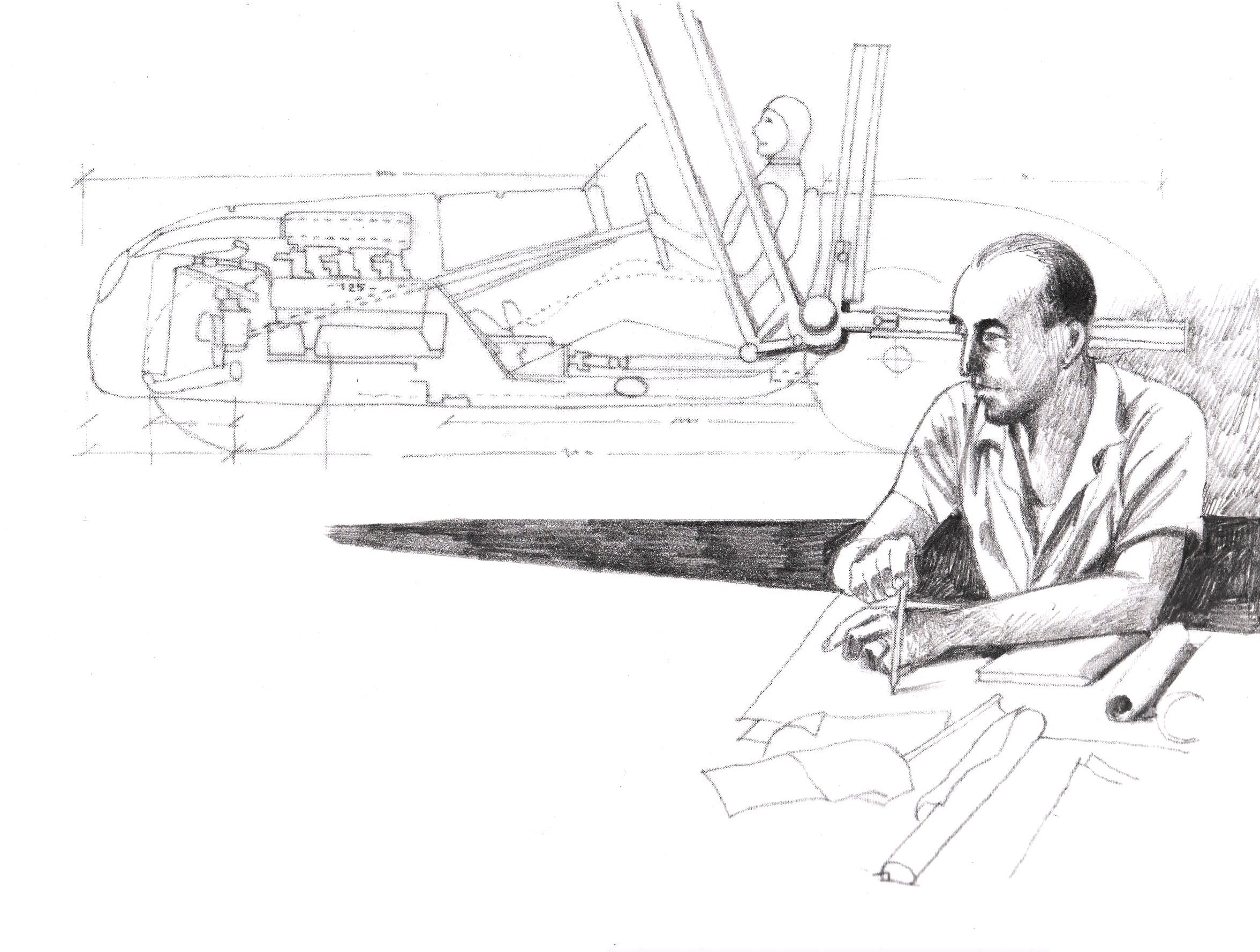

Enzo Ferrari, acutely aware of the impossibility of defeating Auto Union, which in the 1935 season deployed the Type B with its 16 cylinder, mid-rear mounted engine producing 375 hp or Mercedes with its 8 cylinder, four valves per cylinder, double overhead camshaft engine producing 430 hp, played a hand worthy of the finest Italian genius and imagination: to mount two engines starting from the main components of the P3 to reach a total power output of more than 500 horsepower.

That decision, taken in the winter of 1934 in Modena, marked a special moment for the rest of the life of the visionary future manufacturer: he built his first car in Modena, under the guidance of the ever-faithful Luigi Bazzi, in just four months. What’s more, when it was presented, instead of the Alfa logo, the car had a Prancing Horse on a yellow background on the grille. Pride – of course – but also a strategy to protect Alfa: if it didn’t work, it wouldn’t have been an Alfa that lost, on the contrary – as actually happened with the speed record achieved by Nuvolari – it was Alfa that claimed the honours.

The car, which in many respects was absolutely brilliant, was extremely fast but those 540 horses simply devoured its tires. A second place on the very fast Avus circuit was its best result. The only medal was Tazio Nuvolari’s extraordinarily brave speed record in June 1935, when he reached a top speed of more than 360 km/h despite driving in a dangerous wind.

The 1935 season was saved once again by the “old” P3, which defeated the Germans at the German GP. But the reality was that the lack of financial support from the State never gave Alfa the chance to seriously compete with Mercedes and Auto Union, both of which increased their power outputs the following season.

Enzo sought a solution that exploited the regulations, and Alfa, now under pressure to race its cars directly and no longer behind the Scuderia badge, followed him.

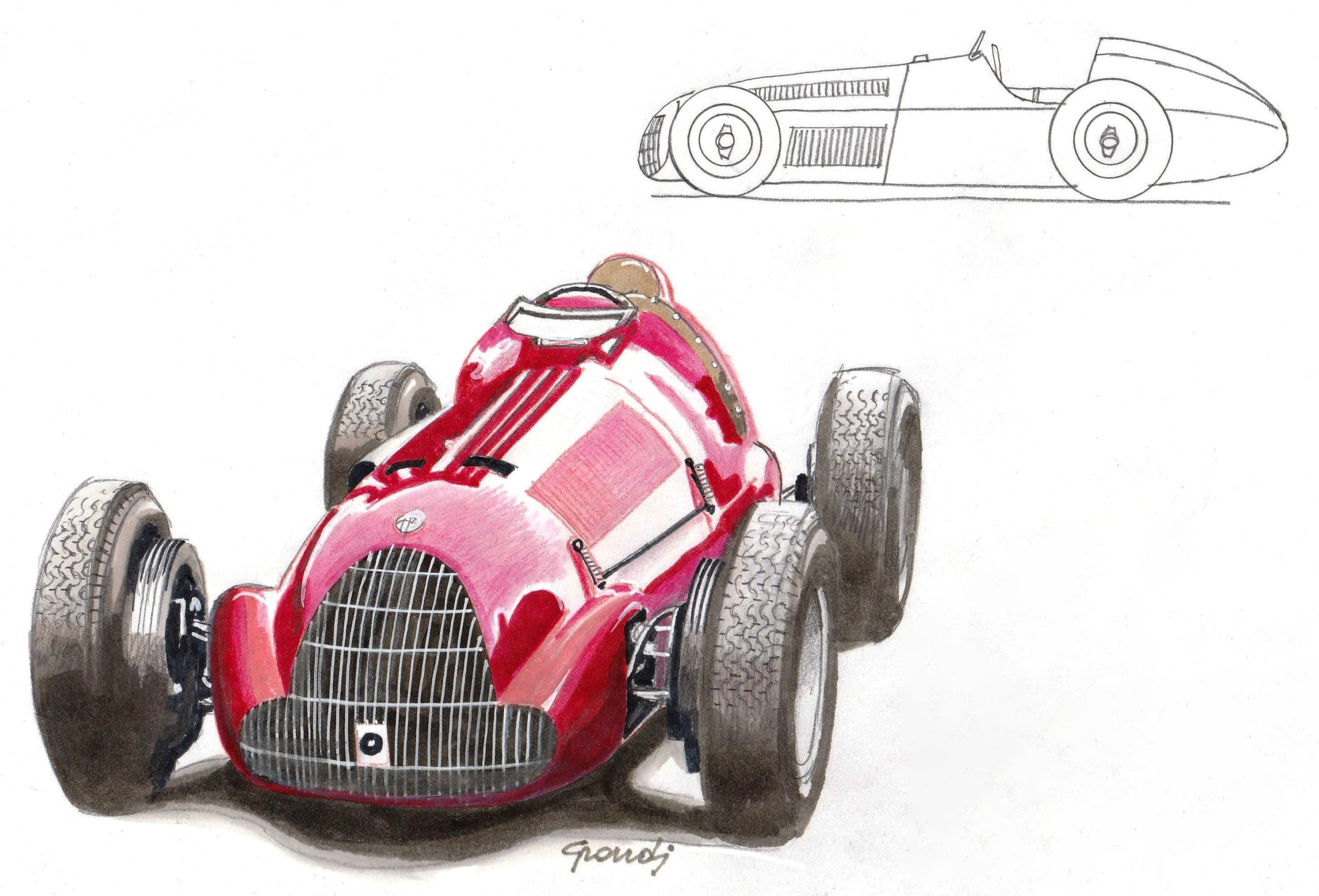

In 1938, a new, smaller racing formula called Voiturette was introduced, which featured 1,500cc supercharged engines while the heavyweight formula used in Grand Prix, now allowed 3,000cc supercharged or 4,500cc naturally aspirated engines. Instead of attempting an almost impossible endeavour against the Germans, it was decided to build a new car for the smaller category. Some famous technicians joined the Scuderia in Modena, including Gioachino Colombo and Alberto Massimino (both of whom played important roles in the birth of Ferraris after 1947) in order to design the 158 which very quickly took on the “Alfetta” name, quite literally “a small Alfa”.

Lightweight, aerodynamically efficient, with its 8-cylinder, supercharged engine capable of producing 195 hp at 7,000 rpm it was at the cutting edge of technology. It’s curious to think that that same car, thirteen years later, would be the single-seater to beat for Ferrari, who had since become a manufacturer in his own right. In fact, the first two years of the Formula 1 World Championship, 1950 and 1951, were dominated by the well-seasoned but always strong Alfetta.

Ultimately, the crisis Alfa went through in those years taught Enzo all he needed to build his own cars. A priceless experience!