Gilles Villeneuve was not alone at the time of the crash

Reopening a case that has remained largely unsolved for the past thirty years without any new clues is only possible if we analyse, in pure Agata Christie style, the exact positions of each of the suspects. The setting was the world of Formula 1 which, at the time, was going through a turbulent period with the arrival of Turbo engines, which only Renault and Ferrari were equipped to race with against the British manufacturers who still used woefully uncompetitive naturally-aspirated engines. The scene was the San Marino Grand Prix that took place on 25th April 1982 at Imola. The British teams, led by Bernie Ecclestone, had gone on strike complaining that it was impossible to reach the new weight restrictions and only 14 cars made it to the starting line with Ferrari and Renault clear favourites. The organizers feared that the huge crowd expected for the race, mostly made up of Ferraristi and, above all, fans of their hero Villeneuve were going to be disappointed by an uneventful race. Nosetto, the Race Director, invited the drivers of the favourite teams to push it. Prost, Arnoux and Villeneuve agreed. Pironi less so and made no attempt to hide it. There was a World Title to fight for and, with the Renaults suffering reliability problems, the chances of Ferrari bringing home a new world title were very real indeed.

This was the climate at that fateful setting, but it’s worth taking a step back to understand what was on the minds of the various stars on the eve of that San Marino Grand Prix.

Who are we talking about exactly? Enzo Ferrari, Gilles Villeneuve who had been in the team since the end of 1977, Didier Pironi in his second year at Maranello and Marco Piccinini, Ferrari’s Motor Sport Director.

What did Enzo Ferrari think of all this? it’s worth bearing in mind that Ferrari always regarded his drivers as employees of the company whose job was to drive in the race and win. When he selected the extravagant and reckless Villeneuve, unknown to most, it seemed just as brave a move as it was unexpected. The Canadian had of course shown talent but had been involved in a series of accidents that had led him to be nicknamed “the aviator”. In short, his roster of victories wasn’t particularly spectacular, the public however, because of his reckless style was enamoured by him. Ferrari, who even went so far as to publicly make him believe he loved him, was actually very unhappy with the way Villeneuve mistreated his cars. His son Piero often tells just how annoyed Enzo became when Gilles arrived at Fiorano for testing: he came in at full speed all the way from Monte Carlo where he lived – his records on that stretch of road are just as famous as the fights he had with Pironi – and, each time, he would park his car with a wild tail spin. Enzo, who regarded his cars as his own creatures, did not tolerate this way of doing things. But on the outside he made sure it was clear that everything was fine. One thing is certain: in April 1982, relations between Ferrari and Gilles had already deteriorated.

Villeneuve began the season convinced that the title was his for the taking. Ferrari had the numbers to do it, but the season got off to a disastrous start with two retirements and a disqualification for irregularities of the car linked to the endless discord between the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), and Formula One Constructors’ Association (FOCA) – the association of British Manufacturers led by Bernie Ecclestone. It was, therefore, vital to win at Imola in order to get back in the running. But he was by no means tranquil. He had a romantic relationship that had driven him away from his family and his wife Joanne had filed for divorce. In addition, he felt isolated at Maranello. Among the many dark shadows of Gilles, not being invited that same year to Pironi’s wedding where Piccinini was best man stands out.

Didier Pironi, who had a very different lifestyle and character to Gilles, had arrived at Ferrari with a promising past but without any true successes. He had built his career methodically thanks to considerable economic means. He was the perfect good-family boy, French by birth, resident in Monte Carlo. In his first season alongside Villeneuve, he stood on the podium four times, not enough compared to the amazing victories of the Canadian at Monte Carlo and Spain. He knew he had the potential to aspire to other successes.

Marco Piccinini, Ferrari’s Motor Sport Director, had the full support of Enzo Ferrari, who was 84 years old in 1982. The choice of the drivers was therefore in their hands and having a Ferrari that was seriously underperforming at the various circuits meant Piccinini’s input was important. And Piccinini was well aware that Villeneuve was beginning to consider the possibility of changing teams. It is mid-season when you normally start playing for the future and at Maranello, the future of their drivers was always an open subject.

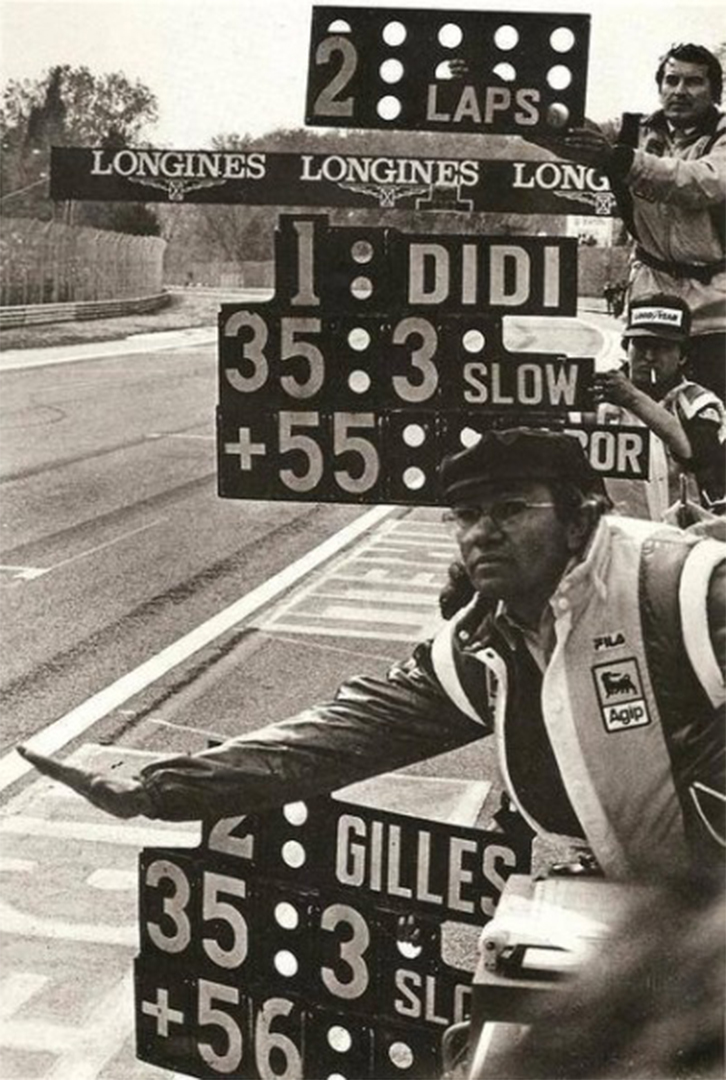

The casus belli. The Imola racetrack was packed. The flags were all red. Over at the race tower, sponsored by Renault, Bernard Hanon, President of the French manufacturer, was enjoying the dominance of Arnoux’s single-seater. There had been several skirmishes from behind between Villeneuve and Pironi but the day looked set for the first black and yellow win. But on lap 45 the engine of the lead car fell silent and the two Ferraris took the lead. Jubilation. A couple of overtakes then Villeneuve took the lead and, following the directions from the box which had held up the SLOW pit board, he set himself up to do his last few laps undisturbed and at a more prudent speed. The pit crew was without Mauro Forghieri who, in these cases, had always been clear. If the pit board had read “maintain positions”, there would have been no doubt. Remember that they didn’t use radio back then. There were just over 10 laps to go when all hell broke loose. Pironi took the lead, Villeneuve took back the position once again, the two took enormous risks, but neither was prepared to concede defeat and the pit boards were totally ignored. A few hundred metres from the finish line Pironi overtook once more and won the race.

For Villeneuve this was an inconceivable gesture that he refused to let go. Between the two teammates, with a long season ahead of them and a world title to conquer, there was total animosity.

In a desperate attempt to ease the tension, Ferrari released a press release, but it wasn’t enough. At Maranello, what mattered most is the partnership of the two drivers.

The Belgian Grand Prix on 9th May at Zolder was looking increasingly arduous. The drivers were not talking to each other and the cars were not at the same level as they were at Imola. The two Renaults were at the front of the grid, the Ferraris behind: in sixth position Pironi while Villeneuve, just seven minutes from the end of qualifying, with worn tires, could only make eighth place, angry and ashamed behind his reviled teammate.

Gilles arrived in Zolder after a difficult meeting at Maranello with Ferrari and Piccinini. This was witnessed by his friend Tullio Abbate, motorboat champion and builder of Villeneuve’s speedboat who had accompanied him while remaining, of course, outside of the meeting. But on his way back by helicopter to Tremezzina, on the west coast of Lake Como where Abbate lived and workd, Gilles, deeply troubled, confessed that he “had been fired”. The phrase is a heavy one, and it’s difficult to imagine the discussion, but if in fact he was already in contact with Williams, it’s not hard to imagine that Villeneuve may have taken a strong position that led to a conclusion that was too radical for a manufacturer, like Ferrari, who had a season ahead to compete for. Alas, life is also made of states of mind and of ghosts and at 1:53pm on Saturday 8th May 1982, when Villeneuve tried to pass inside of Jochen Mass in an impossible attempt to improve the time set by Pironi, all of them were without question on board the number 27 Ferrari.

The next day Pironi did not begin as a sign of respect. On 7th August, at Hockenheim, the Frenchman ended his driver’s career by smashing into the back of Alain Prost through lack of visibility during a violent storm and suffering multiple fractures to both of his legs. Despite losing five races he came second in the World Championship behind Keke Rosberg, and thanks to his and Gilles’ contribution, Ferrari still won the Constructors’ title. A thriller that should have been entirely draped in red.