“Fan car”? Try again Gordon.

Photo credit: Gordon Murray Automotive, Wheelsage

The beginning of the 1970s was a milestone in the history of the automobile: finally, they had grasped the effectiveness of the use of downforce, that is, the crushing of the car towards the ground to ensure traction and road holding. The first studies were carried out at General Motors where they discovered that by channelling air beneath the car the flow caused downforce that increased in proportion to the amount of air that can be released from the rear of the car. The discovery was made why trying to correct the road handling defects of the Chevrolet Corvair that had been heavily criticised for its poor safety record. The engineers of the experimental group were in contact with Hap Sharp and Jim Hall who built the Chaparral racing cars that used Chevrolet engines. And these two were the initiators of the great revolution that introduced ground effect and the in-car adjustable rear wing into the competitive world of motor racing, an anticipation of the current DRS system.

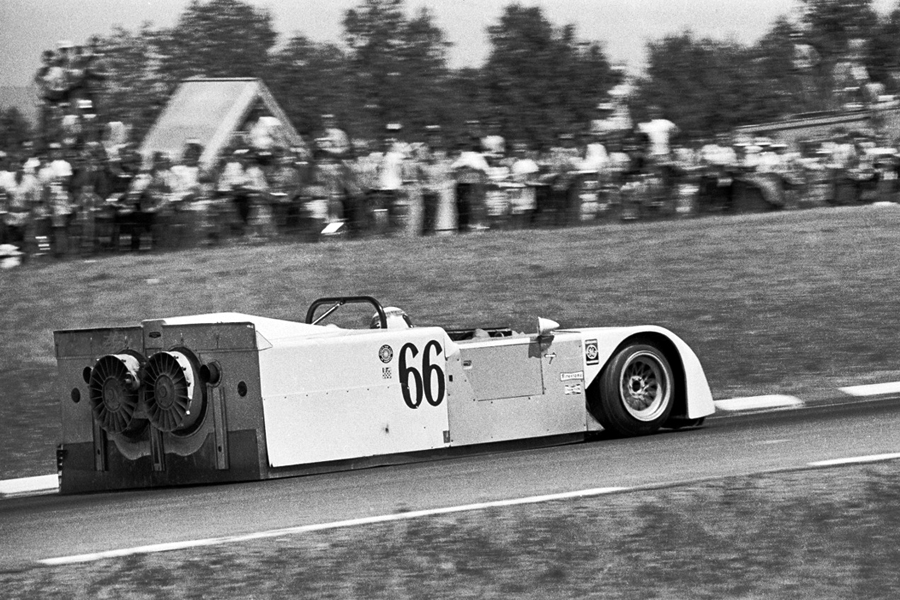

Studying the function of diffusers in a fully-sealed underbody car led the imagination of Jim Hall, the team’s brilliant financier, to think of “helping” the air to escape in order to create downforce by using fans as extractors. In the 1970 season of the Can-Am Championship, a revolutionary car debuted: the Chaparral 2J, which had two 43 cm diameter fans installed at the back of the car, each mounted and controlled by a small, independent 2-stroke engine producing about 50hp. Like a real home vacuum cleaner, these fans sucked air from the car floor and blew it away from the back to create a low-pressure zone and increasing downforce. Despite exceptional qualifying times and many pole positions, the car never managed to achieve success due to numerous early mechanical failures.

This idea, soon banned by the Can-Am regulations, was not forgotten and in 1978 the designer Gordon Murray, commissioned by Bernie Ecclestone to devise something to limit the dominance of Colin Chapman’s “wing cars”, stunned the Formula 1 paddock by bringing the Brabham BT46B to the Swedish Grand Prix. The bulky Alfa Romeo boxer engine did not give them any real chance against the dominant Lotus cars, so Murray decided to reintroduce the solution proposed by Chaparral 8 years earlier. A large fan was introduced, this time operated by the transmission for regulatory reasons that prohibited an auxiliary engine.

During trials, officials were told that the primary function of the big fan was to help cool a radiator placed above the engine. It didn’t take long to understand the real reason, seeing the behaviour of the car in the race, which was quite literally unbeatable, that about 50% of the air sucked out served to crush the car down onto the ground giving it a huge lap time advantage, so much so that in qualifying Murray forced Niki Lauda to race with a full tank of fuel and on harder mix tires. Despite this, he placed third, only 7 tenths of a second from Mario Andretti. Things were decidedly different during the race and the Austrian driver dominated from start to finish, not without causing a great deal of controversy. Andretti, following the BT46B, found himself hit by debris and gravel quite literally fired from the fan like bullets. The commissioners banned the device for safety reasons and the Swedish Grand Prix was the only race the car now referred to as the “fan car” competed in.

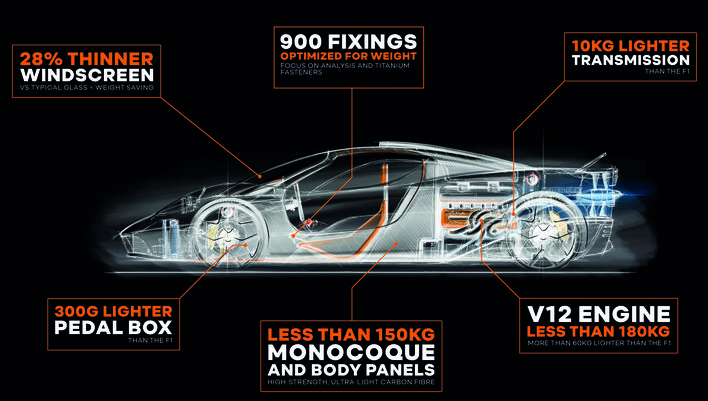

What seemed like a finished story did not end that day: Gordon Murray Automotive, the Company of the British Designer, has recently presented the T.50 Lightweighting that is inspired by the BT46B he made in 1978. The car, decidedly extreme in style, is devoid of the flashy traditional aerodynamic appendages and takes full advantage of the faired bottom and numerous moving elements to give it all the downforce it could ever need. What dominates all this is the 400mm diameter fan in the middle of the tail section. The principle is identical to the one experienced with little luck by Chaparral and Brabham. The fan is powered by an electrical motor integrated into the powertrain that also manages the ignition. This solution was developed in collaboration with the Racing Point Formula 1 team, taking advantage of one of Formula 1’s most advanced wind tunnels at the team’s headquarters in Silverstone. Let’s just hope you don’t end up following one on the highway…