Alfa Romeo. When aerodynamics means style

With the valuable support of Prof. Massimo Grandi’s depth of knowledge and illustrative talent

Photo credit: Massimo Grandi

From today until June 24th, the 110th anniversary of the founding of Alfa Romeo, we will be publishing a series of posts dedicated to this brand, which, in the course of its long history, built on creativity and imagination, has managed to be a protagonist in every field it has entered. We begin by taking a look at what Alfa did in the field of aerodynamics in the pre-war years. This description takes us forward in time with regard to our weekly pieces on this topic, which we will resume, going back to the point we had reached – 1927 with the Claveau –, after this digression into the history of the “Biscione” (as Alfa is known, in reference to the giant snake that features on its badge).

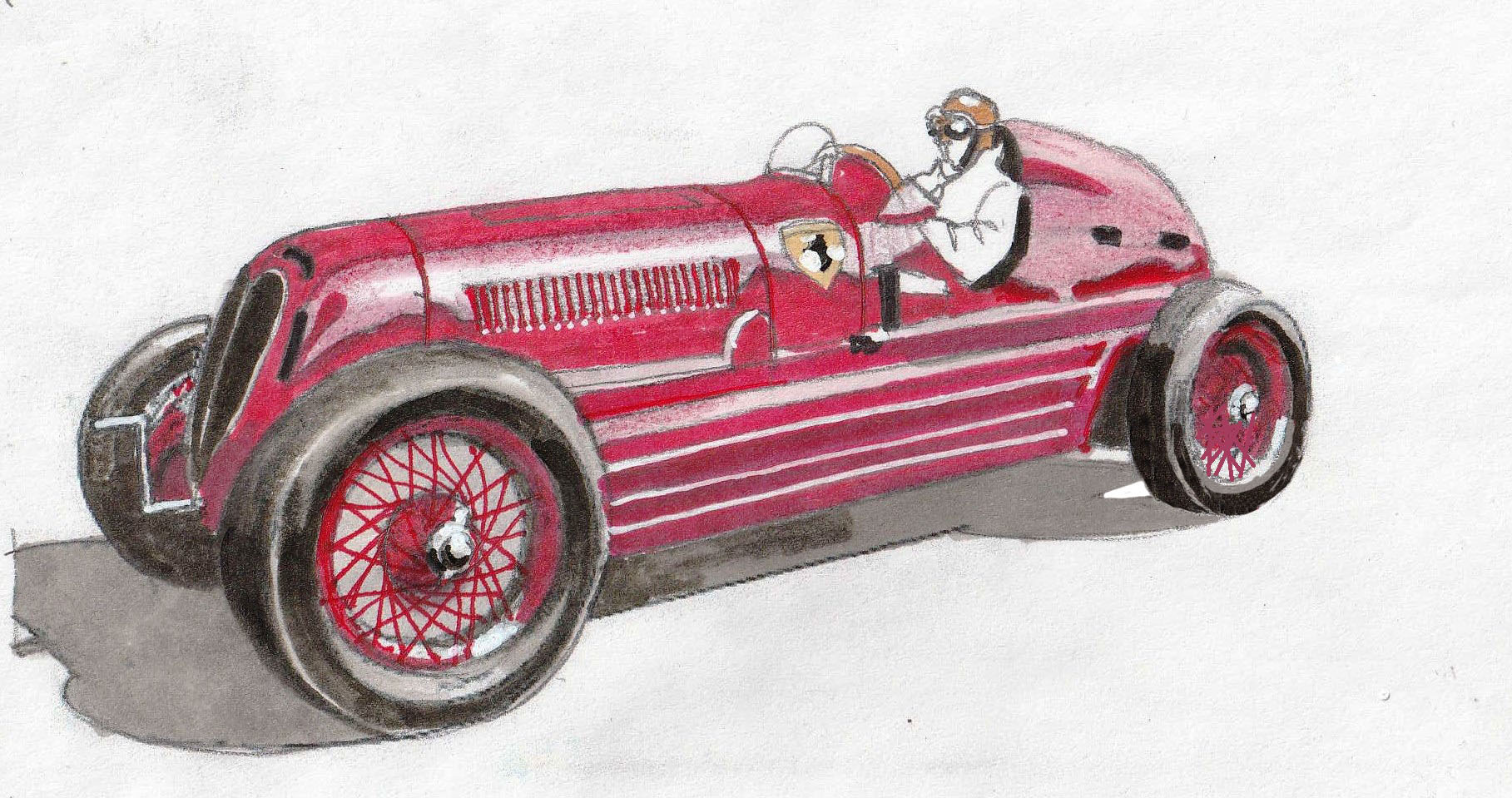

In the 1930s, with the world waking up to the need for new streamlined contours, better able to cut through the air, Alfa Romeo was already so successful with its powerful conventional racers that it had little interest in this new requirement, which was far more than a question of style. However, over in Hilter’s Germany, new Mercedes and Auto Union models were clearly showing the value of combining fluid forms with increasingly powerful engines. Alfa, which in those years competed under the colors of the Scuderia Ferrari, created by the young Enzo Ferrari, therefore responded by designing a completely original car: the 16C Bimotore, where the “16” indicated the number of cylinders (8+8 divided between its two engines), and the “c” stood for competizione. The twin engines, mounted one to the front and the other to the rear of the driver, were connected by a single transmission and provided up to 540 HP. The size of the fuel tanks made it necessary to rethink the body, which was rendered more streamlined: the angular edges typical of Alfa designs disappeared, and the overall look of the car, still impressive in size, was harmonious. Other aspects were less successful though: the car was unstable at speed and consumed countless tires due to the violent torque transmitted during acceleration. In short, it was not a race winner. It went on to be used in an attempt to set a new speed record. This it did, driven by Tazio Nuvolari — at some considerable risk — on the Florence Mare highway on 15th June 1935.

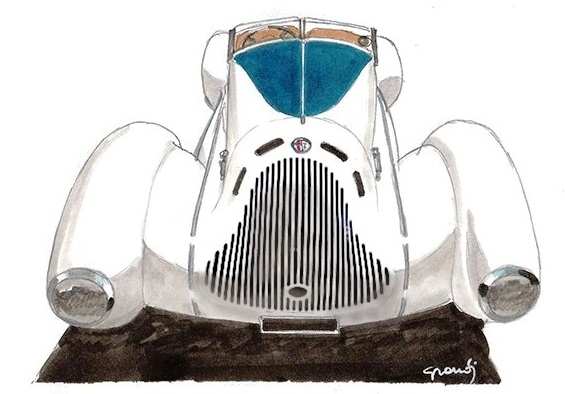

The 6C Gran Sport designed by Revelli di Beaumont was decidedly more advanced aerodynamically. This car, first unveiled in 1931 with Zagato coachwork, was rebodied in 1938 by Giuseppe Aprile. The result was a unique and amazing model that showed beyond doubt that aerodynamically fluid and efficient lines were becoming a reality — a reality then fully expressed by the Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 B Le Mans Berlinetta Touring, created to race at Le Mans in 1938. This latter car, with its compact interior and generously proportioned front, housing a powerful engine, had a clearly aerodynamic shape enhanced by the lines of the “thick wing” bodywork. Unfortunately, despite its superior performance on the circuit, the race ended badly. With a 14-lap advantage over its nearest rival, and with the end of the race in sight, it suffered an engine failure and was forced to withdraw. This brilliant creation thus saw what would have been a well-deserved dream victory slip from its grasp.